The Best Things I Learned In 2019

I didn’t know this at the time, but I sowed the seeds for this review on January 1st, 2019, when I wrote about how my day went, what I did, and what I learned.

It’s funny how most reviews focus on things that happened in the past three months - that’s more like a quarterly review that happens once a year, isn’t it? Since it’s fresher in the mind, and easier to spot the recent faults, these morph into goals and new years resolutions. But what about the nine months before that? What if the issue you’re thinking about isn’t one-off, but a structural problem?

At least, that’s what my last years review was like. But, things have changed a lot. I’ve felt remarkable growth this past year. Part of it has to do with this blog, and part has to do with the processes I put in place to become happier and more productive.

I’ll focus on the best things I learned, some of my processes, and in the end, I’ll share how the content on this blog changed, what makes great content, stats about the blog, and some cool stuff from the Idea Muse.

Most things online are crap

I spent most of my life living through informational junk. The more time I spent in here, the more normal it seemed.

I was like a trash-picker, looking for gold.

Swimming through this junk, as I found bits and pieces of gold, I realised the junk didn’t have to be a normal state. Gold exists. But, the probability of finding gold as a trash-picker is low. I’d rather be in an environment with a higher base-rate: like a miner in a gold mine.

First, lets clarify what’s junk. Informational-junk is like empty calories.

If you’re looking for energy, the empty calories will fill you. However, if you’re looking for nutrition, empty calories are the worst kind of food.

Likewise, if you’re looking for entertainment, informational junk will fulfil you. However, if you’re looking for growth, junk is garbage.

With this idea in place, figuring out if something is junk means asking myself these 2 questions.

- What is this piece trying to say?

- What did I learn?

If the answer to 2 is nothing then it’s informational-junk. If I can’t figure out the answer to 1, it’s either junk or too smart for me to understand, which is as good as junk right now.

Iron ore is just another rock to a hunter-gatherer without ironworks

These questions work only after I’ve read the piece though. It’s again a bit like eating. I’m trying to test whether the food I ate was junk or not, after its already in my stomach and bloating me up.

Thankfully, the number of ways to package food is limited. So, over time, you figure out what’s junk and what makes you feel good.

With information, there are a million ways to package it. This makes it much easier to consume information junk: You’re duped into thinking its nutritious.

However, there are a few popular packagings which are usually junk. My top one for these is listicles. It’s someone forcing themselves to come up with random ideas to end the post on a round number. How the heck are most listicles round numbers?

This is one major reason I don’t use lists as headings on this blog: it’s a forcing function to reduce the quality of your post by padding it with junk.

Building a stream of nutritional information is harder than eating well.

This idea led to writing on information overload and my process for filtering out junk. The short version: choose interesting people as sources of information, set up filters on your sources, and increase your consumption bandwidth.

Platforms over optimizations

If there’s one big idea I’ve discovered, it’s this. For any long term project, build platforms before optimizations.

To curb my anime addiction, I created a hack for myself: “I can only watch anime while standing or walking”. This made it super hard to continue binging through the night.

But, there was no way to enforce this. 4 days later, I got back from the gym, was too tired to stand, forgot all about this hack, and fell back into my old habit of watching anime while sitting.

When was the last time you read a new hack and decided to try it out? And about a month later, you come across it again, and realise you forgot to do it after the third day?

Hacks are fleeting. Any optimization that wants to make it into your routine needs time, practice, and constant reminders.

Note:

A hack is an optimization. Hacks aren’t necessarily bad, despite the common usage of the word. I like this word, and to PG, me, and a few other people, hearing the word hack is exciting. There’s no negative connotation involved. It’s exciting to figure out whether the “hack” in question is brilliant or a regular duct-taping ugly hack.

What if, instead, I block anime from my laptop, fix up the old laptop as the anime stand, take away the chair, and create this new platform for watching anime?

A platform is a base - something for you to stand on. Somewhere where what you do accumulates. It can be a process, or a physical platform. Habits are platforms.

An optimization is a hack that helps you work better. Intermittent fasting, summarizing everything you read in your mind, deciding not to jizz, or not to watch anime are optimizations.

Optimizations are meaningful only in the context of a platform. Without a platform, they don’t help much.1

The platform in the above example is the old laptop sitting on a desk. The optimization is removing the chair, so I only watch anime while standing up.

The optimization might be right or wrong, it might change over time, but the platform is there to stay. It’s more resilient. It might even be antifragile2, as changes give you new ideas to improve the platform.

On the other hand, platforms can break, just like optimizations. The difference is that platforms break with a sound. They throw an alert for you to know that its breaking. Optimizations don’t have this built-in.

For example, with my anime platform, if I get on my bed to watch anime, the first alarm bell rings. “Oh, I can’t access things here. Why not?”. The second, weaker alarm bell is when I get to the anime stand and look for a chair to sit on. Whoops. Of course, I could unblock things on my laptop, but that’s extra mental effort and a conscious breaking of the platform - the alarm bell blasts off in my head.

At least, this platform exists in physical space. Thinking hacks, on the other hand, are all in the mind. There’s no physical reminder to make things easier. No physical alarm bells.

This is where process driven platforms shine.

I do daily and weekly reviews on interesting hacks and ideas. Having this process of coming back to things means I can write down every hack, and figure out how to put them on top of each other. No hack is ever lost, just replaced with a better hack.

One of the most exciting questions I’m tackling right now is whether I can create a platform for thinking better?

Questions are more important than answers

Why does a cut on the finger bleed a little but the same depth cut on the wrist can bleed a lot more?

Questions bring the obvious and what’s not being said into focus. They are like a magnifying glass, bringing things into focus.

By definition, the obvious is never the focus.

By design, we can’t focus on what we can’t see.

Breaking through this is what makes Sherlock Holmes so great. I don’t know what’s going on in his mind (or Sir Arthur Conan Doyles’) - but he’s able to focus on both of these, instead of just what feels exciting.

Focusing on what didn’t happen

“The dog not barking meant the victim knew the murderer.”

The happy path to this insight would look something like:

Mrs X has a dog, doesn’t she?

Yes.

What was the dog doing?

Not sure.

It didn’t even bark?

Yeah. How interesting.

Why not?

Because it knew the person.

There were probably quite a few more lines of questioning that didn’t lead anywhere. The challenge was to find the first interesting question - “Does Mrs. X have a dog?” - and let it lead you to the answer.

Focusing on the obvious

“The world is full of obvious things which nobody by any chance ever observes.” - Sherlock Holmes

It’s a rainy day. Watson is out all day. When he returns, Sherlock immediately comments, “Were you at the club the entire day?”. Can you guess how?

If I wrote the hint in, it would stand out instead of being obvious: His shoes were clean.

I can think super hard about what’s obvious, but unless I frame questions, that thinking goes no where. The obvious is not interesting.

You need questions to make the obvious interesting.

For example, in this case, I’d begin with: “Can I figure out where Watson is coming from?”

My first instinctive answer is “Yes, why not?”. That begins a process of elimination. The clues come into focus only when I have the right question to ask.

Where all could he go? - His doctor’s practice, the club, home, enjoying the streets outside.

.. Oh, but it’s raining outside.

So, did he go outdoors or indoors?

This cues observation.

Is he clean? Yes. Did he take a bath again? Probably not, he only takes a bath in the mornings.

So, he wasn’t out in the rain for long. So, indoors.

But his clinic is far away, so either the club or home.

There’s nothing at home, thus the club.

If he were married and with kids at this time, the answer might’ve been different.

This example is a bit contrived, but it shows how to surface the obvious.

I don’t intend to use this idea just for deduction3. It’s for everything I do, and everything I write. If what I write isn’t lead by an interesting question, what I produce is usually meh or clickbaity.

I’d take it a step further: If what I think isn’t directed by an interesting question, what I produce is garbage. See cringe posts. I wrote most of these because I needed something to write, not because I had an interesting question to answer.

“If you don’t have questions, you won’t find the answers.” - Claude Shannon

The flipside

Since questions are so great at focusing, it’s important that I don’t get held up by the wrong questions. A question is like holding a magnifying glass in broad daylight - focus on the wrong thing and you’re going to burn.

That’s the difference between “Why do I suck?” and “How can I become better?” or “What can I learn from this mistake?”. Whatever I ask, I’ll find the answer to.

To answer the question we began with, blood flow is proportional to the size of arteries. Bigger arteries imply faster blood flow. Thus, the same cut on a bigger artery is more damaging. As you can imagine, the wrist has a bigger artery than the finger. Fun biology facts hiding in plain sight. Yup, this is just one of the coolest things I learned this year.

Compounding is powerful. Building intuition for compounding even more so.

Coming back to platforms, the entire idea behind platforms is to leverage compounding.

Since platforms accumulate, compounding goes hand in hand with platforms.

This blog compounds. Every idea I learn and connect compounds my knowledge. Every gym session compounds.4

I sometimes don’t see the effects, and I often underestimate the impact, but I’ve seen them enough times to hunt for compounding everywhere. It’s a superpower.

This raises an interesting question. How do I figure out if something compounds?

The answer is in relativity and growth rates. Something compounds if its relative growth is greater than 0.

As Paul Graham put it:

When I first meet founders and ask what their growth rate is, sometimes they tell me “we get about a hundred new customers a month.” That’s not a rate. What matters is not the absolute number of new customers, but the ratio of new customers to existing ones. If you’re really getting a constant number of new customers every month, you’re in trouble, because that means your growth rate is decreasing.

Probably the best example is compound interest, which by definition compounds.

At every iteration, your total money grows by r%, the rate of interest. This extra money is added to your total, so on the next iteration you have more money than before, which means the growth is more.

Then, how does knowledge compound?

Money is continuous5, but ideas are discrete.

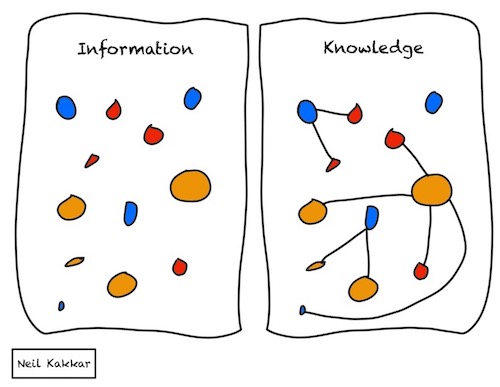

I like to think of knowledge as connections between ideas (or information).

If every idea you discover sits in its own silo, your knowledge isn’t compounding. On every iteration, you’re adding one more piece of information.

This is what makes (re)reading easier than assimilating information to create knowledge. To create knowledge, you need to form connections between the ideas and facts you have.

If every new idea creates k% more connections, you have compounding. This makes intuitive sense, since the more information you have, the more chances you have for connecting that information to create knowledge.

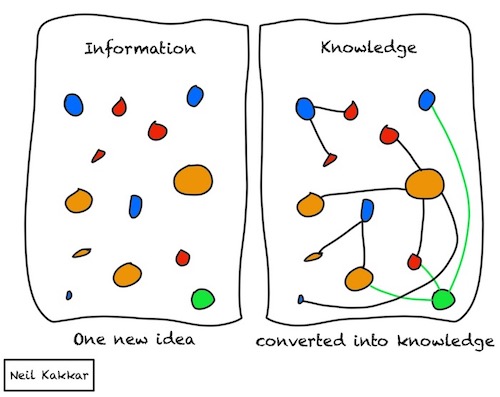

Reality though is a bit more messy. Not all ideas spark connections. You might go a long time consuming information before you figure out how it all connects.

This happened to me when I started researching about climate change, and had to project things out of my mind before I could make sense of it.

A scary corollary of Paul Graham’s advice for start ups is that if you’re learning 1 new thing every day, but fail to make the necessary connections to convert it into knowledge, your growth rate is slowing. Is that a problem? I’m not sure. Growth start-ups and human brains aren’t isomorphic.6

Now that we understand compounding, we need to develop a feel for it. This helps recognize it in the wild.

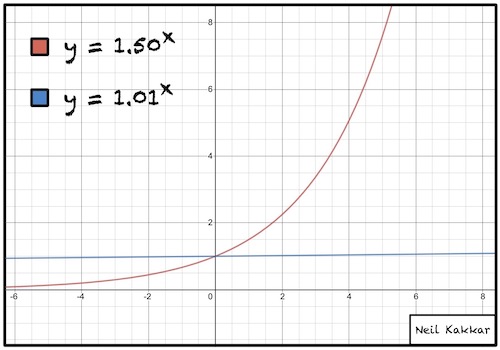

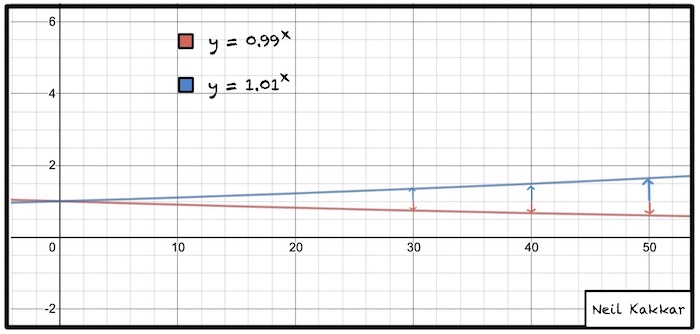

Initially, compounding feels linear

Most real-world exponential curves look linear in the beginning.

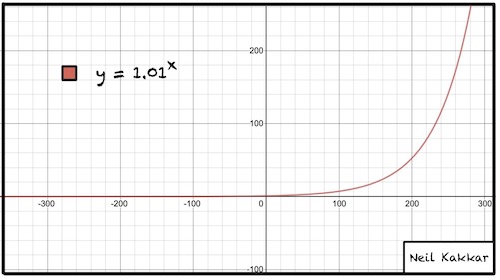

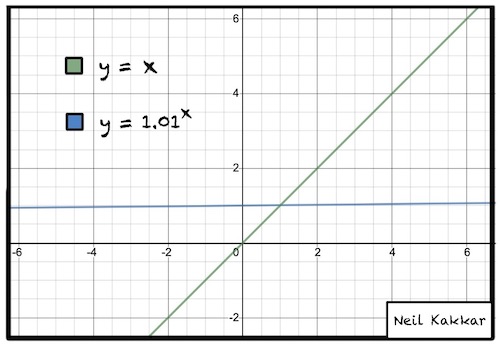

Both these curves are exponential. We tend to think of the red one as exponential, while the blue one seems linear. 1.5^x represents 50% growth per iteration7. That’s insane. Most startups, the angels of growth, can’t sustain that.

The blue curve is 1% growth per iteration, or 1.01^x.

1% better every day is a lot more realistic than 50%.

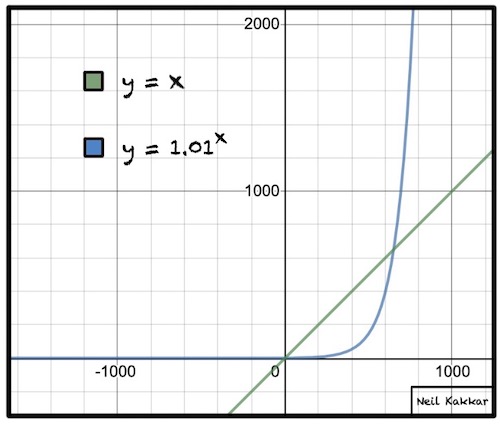

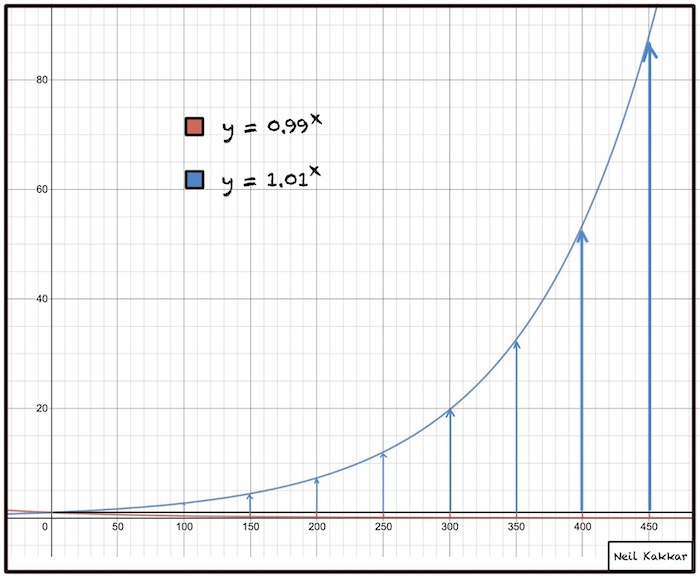

Next, the smaller the compounding rate, the longer we have to wait to reap the benefits. The graph looks linear for a long time. In other words, the amount of time the graph feels linear is inversely proportional to the compounding rate.

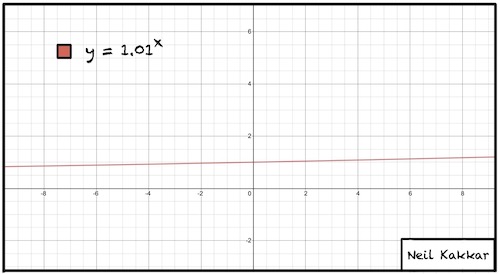

When you zoom out, you see over many iterations it starts to feel exponential again. Notice the scale on the graph.

It’s the same function. y = 1.01^x. 1% better every time.8

… and if you’re just getting started, absolute growth (via hacks and optimizations) feels much stronger than exponential, despite being one-off linear growth.

But if you’re in it for the long run, 2 years later, 1% better everyday trumps all the hacks in the world.

Of course, 2 years is hard.

Slowly, then suddenly

Note:

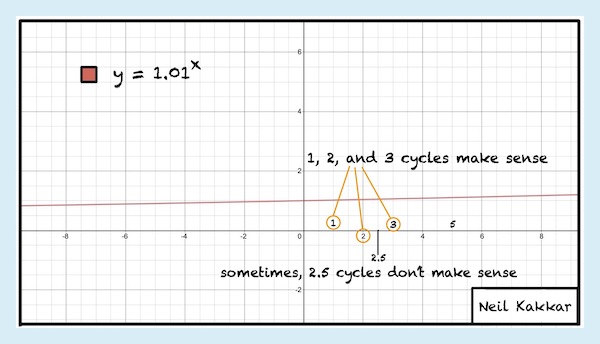

A short note about why y=1.5^x is compounding at 50% and what I mean by iterations.

Imagine you start at 1. At 50% growth rate, after 1 growth cycle, you will have 1 + 50% of 1. Or 1.5.

Now, you have 1.5. After the second cycle, you will have 1.5 + 50% of 1.5. If you take the common 1.5 out, you get (1.5)*(1 + 50% of 1). We already know the value of the second term is 1.5.

So, this becomes 1.5*1.5 or (1.5)^2.

Now, we have (1.5)^2. After the third cycle, we do the same thing, taking (1.5)^2 common this time, to get (1.5)^3.

The iteration is one cycle. The graph is continuous, but we care only about the discrete time. If the cycle happens every day,the growth rate is per day, then it compounds daily, and the x axis is the days.

When talking about startups, this growth rate is per week or month, and thus the time scale shifts accordingly.

If you want to start with any other number instead of 1, just multiply it. So, to start with 10,000, your function is y = 10000*(1.5^x). It has the same characteristics, scaled up.

Compounding is asymmetric

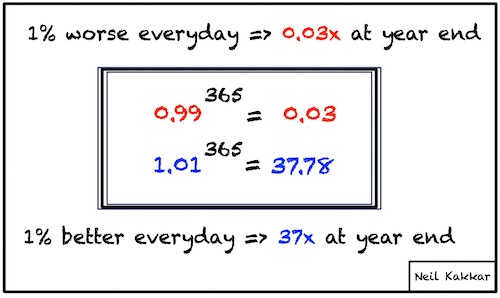

Growing at 1% isn’t the opposite of decaying at 1%. There’s an asymmetry between % growth and death.

You’ve probably seen this motivational poster before:

The interesting bit is that they are asymmetric.

Over 20 or 30 days, there isn’t much of a difference. Both seem linear, and they’re both equidistant from someone who stays where he is.

Have a look at this graph.

This is the slowly bit.

Next comes the suddenly bit.

There’s a lower bound on how bad things can get. The upside is unlimited9, and the downside is limited (despite being a really bad outcome).

They aren’t the same. Intuition trips us up. Because we can’t project things very well into the long term, we think staying how we are is okay. But that means giving up on all that growth.

If you’re comparing yourself to someone starting with you, but on that exponential curve, it’s going to hurt.

Being aware and making that trade off is fine. Being unaware and caught off guard? Not so much.

Thinking in Systems

The book, Thinking in Systems blew me away. This was the first time I read about systems, and I latched on to the ideas of feedback loops, stocks, and flow. I wanted to explore this further, see things more intuitively, which led to ideas about how to see systems, and how to understand systems.

If I had to choose one exciting idea to talk about, it would be reductionism vs emergence.

When solving a problem, there’s this temptation to figure out the root cause. Every post-mortem is designed around root cause analysis, figuring out what single thing went wrong, and in some companies and cultures, who to blame.

However, in complex adaptive systems with millions of moving parts, there isn’t one single root cause. There are causes that are each necessary, but only jointly sufficient.

As an engineer, I love breaking things down into its constituent parts. The idea is, with modular code, or modular blocks, once you understand each block, all you have to do is put them together and you’ll understand the whole. This is the reductionist approach.

It works everywhere but systems which show emergence. With emergence, the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. Which means putting them together is a non-trivial operation, which makes reasoning about the whole via how its parts behave extremely difficult.

For example, a machine is not an emergent system. Every gear works exactly as it’s supposed to, and putting a few gears together, you can understand how the entire machine works. There’s no funny business involved.

A city, where humans and the environment responds to changes, means it’s difficult to understand how the city will behave even if you understand every single persons motivations. That’s a complex adaptive system which shows emergence.

Life is a complex system, too. It arises from atoms arranged in a certain way. Arranged a different way, the exact same atoms are dead. It would cost less than $200 to gather all the materials present in a human10, but we aren’t close to creating one ourselves.

The key to emergence is communication. When parts of the system can communicate and respond to changes, emergence occurs.

This is another reason why I’m super excited about quantum simulations. With that kind of power, we could model a city, and try to understand the emergent patterns that arise, since we can model the communication, too. Imagine modelling a city that’s close enough to the real deal, and before approving any major public works, test how it would do on the model, and based on that approve or reject projects. It’s a public policy gold mine.

Environment design

I’ve become very mindful of the environment I live and work in. In most cases, I’ve rejected the ideas I grew up with (sometimes breaking Chesterton’s fence, and learning the original way was better). I’m experimenting to figure out what works best for me. This is a continuous process - I keep learning and changing, which means my environment needs to keep up with me too.

However, there are a few core principles I stick to.

Reduce friction

I want to make things that I want to do, easy to do.

Some days I wouldn’t feel like writing down what happened during the day, or count the number of meaningful hours I worked.11 I just want to watch anime instead. Every night at 8:30 PM, my Google Sheet automatically opens up. And since it takes less than 2 minutes, I just do it.

If it irritates you, its got to go

Irritations are a mind and mood killer. Instead of accepting it, I find a way to get rid of it. Sometimes, my solution can leave me worse-off, in which case I rethink how to get rid of the irritation.

For example, learning to love showers instead of avoiding them was a better hack. Keeping the body unclean bites back 100x.

Free up as much time as possible for meaningful work

Spending lots of time on chores irritates me. The past 6 months, I’ve been cooking the same meal for lunch: grilled chicken and vegetables. It’s easy to cook, takes 14 minutes (including cleaning up afterwards), and I prefer eating the same meal everyday to deciding what to make, figuring out how to make it, and then cooking it. I also prefer this to eating out, since its healthier.

But I’m starting to get sick of this (I’ve changed, so my process needs to change). So, I’m experimenting with different marinades for the chicken. If that doesn’t work, I’ll try something else. Maybe it’s time for salmon or black beans.

Reduce number of decisions

This one comes from Steve Jobs. I don’t know if ego depletion is true, or if thinking it’s false makes it false. But from what I’ve seen, I can make better decisions in the morning compared to the evening.

I’m fresh, well rested, and ready to get some work done in the mornings. During evenings, I can do this only when I have an active exciting project I’m working on.

I’m not sure if this is related to the number of decisions I make during the day (an experiment for another day).

But for now, I follow this heuristic. Don’t make the same decisions again, every day. Just fix them. Make the decision once, and then decide to do the same thing every day.

For example, I only wash my clothes on Sundays. Every Sunday, I check if I have enough clothes to wash. If no, defer to next sunday. If yes, wash. No other time do I think about washing clothes.

Once done, I place them in order. When deciding what to wear, I only pick up what’s on top (unless I don’t feel like wearing it).

Yeah, some of my friends think I only own 2 t-shirts.

Putting them all together

To follow these principles, I need to destroy a few tendencies. For example, I dislike spending money. A lot. I’d frown upon owning duplicates of things. Why use a glass when you have a water bottle?

This can get irritating fast. If I forget my water bottle at home, I’m forced to use paper cups at work (Save the planet, say no). If I forget the bottle at work, … I need to buy a glass.

I’d rather own two bottles and keep one at work and one at home. It gives me peace of mind. It’s a tiny thing, but tiny things add up. It reduces number of decisions I have to make and removes one small irritating thing from my life.

It’s a structural design win.

I’d rather have routines for the mundane tasks so I can be creative in my work, than vice versa.

I’m extremely fucking lucky

The entire past decade, something happened, something insignificant, that pushed me in a loop upwards.

In school, when I was an “average” kid and didn’t know it, my best friend introduced me to a coaching center. They had interesting content, at a bit higher level than school, and well explained. I identified as the kid who didn’t need tuitions. Tuitions were for dumb kids. But the ball was already set in motion: they assumed I had already joined, so to avoid confrontation, I started going to extra classes.12

Luckily, this teacher was amazing, and became a lifelong mentor and friend. He’s now the founder of Doubtnut.

The starting step? A sample class coupled with my weak psyche and low social skills.

I learned to go beyond school, went deep into a few topics, and rose up in school.

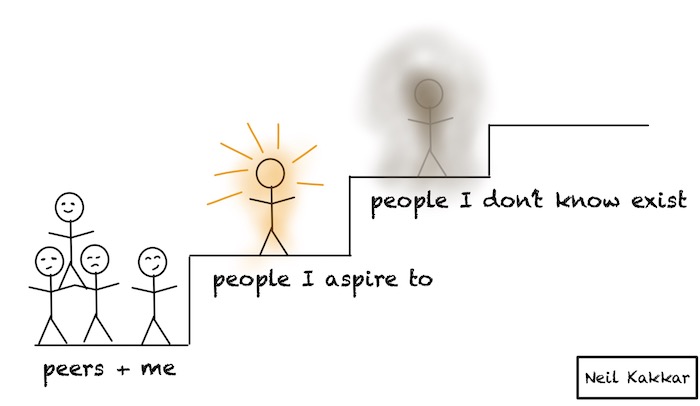

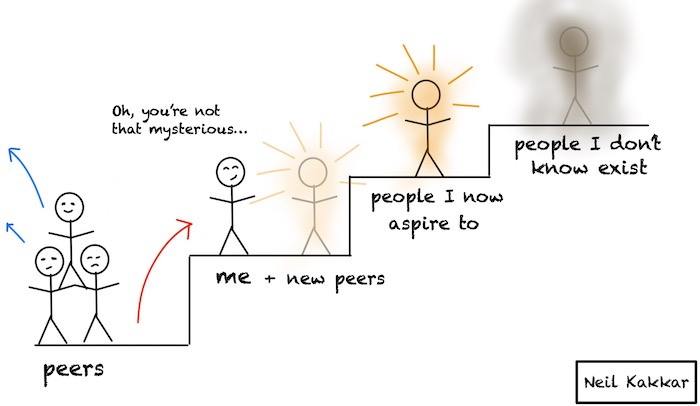

Once I succeeded, he urged me to look higher. He referred me to his mentor, and thus began my journey towards the next set of peers.

Every time my peer group upgraded, I was in the company of people I aspired to be.

Every time, I found new people higher up to aspire to.

Every time, something insignificant created a significant loop to get me there.

This is the first time I’ve become conscious of it. I needed enough instances of the pattern to pattern-match.

Now that I’m conscious of it, I can ask an interesting question: How do I propel myself forward?

I don’t know yet, but I think continuing some of the things above will help. I can’t depend on luck every time. It’s never going to be always blue.

Tracking

What gets measured gets managed

I probably read this in Peter Druckers short book, Managing Oneself. The idea has stuck with me. I track things I care about. And I am careful not to track things that are easy to track but ones I don’t care about. That leads to bad things, like Goodhart’s law.

Goodhart’s Law: When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.

I discovered the Oura Ring this year, and I’m a huge fan. This helps me track my sleep better.

I also track things I’ve learned, what makes me happy and sad, daily. This is a good metric for me to judge how well I’m doing.

Every week, month, and quarter I do a big review which builds up from the previous layer.

7 good daily reviews lead to a great weekly review.

4 good weekly reviews lead to a great monthly review.

3 good monthly reviews lead to a great quarterly review.

And 4 great quarterly reviews make this amazing annual review possible. That’s how I sowed the seeds on January 1st, 2019.

I’ve also recently started tracking all the questions I have about things. Some of these, if the question is interesting enough, turn into blog posts, like this mental model for germs.

The Numbers

Time for some numbers.

I spent about 1050 hours over the year learning and creating outside of work. That doesn’t sound like too much to me, but then, when I convert it to number of extra 8 hour working days - that’s 125, which sounds like way too much. On average, this was about 3 hours per day.

My crap sleep days are surprisingly consistent: 11 days every month, or about 36% of sleep time. Out of this, 5 days (17%) are extreme shit: a result of binge-watching till late, unable to sleep, a heavy meal after 7 PM, or actively thinking about an idea or event.

It was surprising to figure out that the kind of food I ate affects my sleep. I have no idea how I used to sleep after having dinner. Dinners are heavy.

I also discovered that the kind of food I grew up with probably isn’t the best for the kind of body I have. It’s surprising how many people go without questioning this - there might be a better cuisine-match for you out there.

Bite-sized ideas

These are ideas I haven’t explored in depth, but observed in my life. Some are a direct result of tracking. Others sprouted via observation and pattern matching.

It’s usually the same things that make me sad, but lots of different things that make me happy.

This sounds like a reversal of the Anna Karenina Principle. Or maybe this is the Anna Karenina Principle. The different things arise when the things that make me sad are absent? Possibly.

Gamification works. Health, wealth, and wisdom can all be gamed.

Rationalist communities are some of the best places to hang. Becoming LessWrong is worth it.

Burnout, happiness, and energy all depend on a natural rhythm. When I fail to pace myself, burnout occurs. I become sad and lose energy. This can be because of spending too much time playing, or too much time working.

The natural rhythm can be trained to sustain longer periods of focus and energy, but be careful not to tear muscles when you do. The sweet spot is just a little bit out of the comfort zone.

When I hit a ceiling, I hypothesize physics will complain.13 But I’ve never hit the ceiling, so I can’t test the claim.

People are different, and thinking in aggregate is hard. If the entire world were like me, the global economy would tank and Oura would achieve 100% market share and become super rich. How many viewpoints and actions can I not see?

If past-me doesn’t make me cringe, have I grown at all?

It’s hard to pattern match the right pattern of 2. It’s very easy to pattern match the wrong pattern of 2.

“My uncle and aunt smoked and lived to 100. So, smoking isn’t bad.”

My imagination limits how much I can achieve in a year, if I decide what to do via resolutions or goals every 12 months.

Just like my “annual review” focuses on the last quarter, I bet I can achieve my New Year goals in the next quarter.

The only way to see limitations of something new is to reify it.

My imagination isn’t good enough to see through all consequences before things exist. So, I’m all for cheap experiments. The downside is limited (you lose £30 and a few hours), but the upside is confidence.

The key is figuring out how far down the abstraction ladder do you want to go before the downside trumps the upside. MVPs are an instance of this principle. So is downtrodding risk to create value.

If you want to follow your own interests, you’ll have to break away from the crowd. It will get lonely at times, but that’s the trade-off you’re making. Giving up the security of the group for exploring what interests you and not the group.

Becoming a robot at things you don’t want to do is an underrated super power.

The Blog

One of the best things I did for myself was starting to write online. It has created a sandbox for my ideas.

Hearing about my ideas from others is a much stronger and faster feedback loop than extended thinking on my own. I learn faster when I teach, since people rush to correct me when I’m wrong about something. (Super grateful for this, thank you.)

This is also nice feedback loop for me to figure out if I’m reading interesting things or not. If my consumption is garbage, what’s going to come out is garbage. Sometimes, garbage dressed in silver.

The right kind of content

Early on, the bandwagon I jumped on was the self-help insight-porn junkie shooting-up-every minute. You need to grab attention, and need an Unsplash image every 10 lines to ensure you still have their attention.

This wasn’t who I wanted to become. Medium was becoming a meme I wanted to escape. Not because of the platform itself, but the kind of writers that were flocking to it.

“I did X, it was awesome, this is how I did it, you can too.”

And you can replace X with anything that makes you vomit 🤮. And the person in question barely managed to do it, once.

Or “I spent 5 hours building a business, here’s what I learned.”

It was all shite. Shite coloured in rainbow. A ponzi scheme of aspiring writers making money by teaching other writers how to make money.14

With Medium, the floodgates opened. When you reduce the barriers to entry, everybody enters. The proof of work is gone.

I’m happy Medium exists, but I don’t want to drown in the flood.

As I read more blogs I admired (LessWrong, Slate Star Codex, Seth Godin, Melting Asphalt, Wait but Why, and a few others) - I realised none of them did this. The rules I had learned on Medium were optimizing for something I didn’t care about.

However, it’s not true that everything on Medium is crap. I don’t want to shoot Medium, the messenger, for the message. I found some pretty kick ass people on Medium, too. People who perhaps started writing on Medium because there was less friction. People like Byrne Hobart and Duncan A Sabien.

The interesting question here is what’s the kind of content I do want to create?

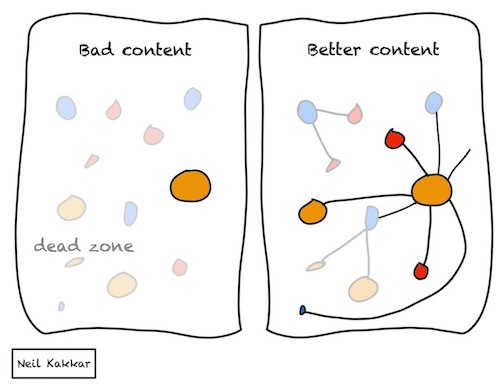

First, I want to zoom in on informational-junk. Or junk wrapped as insight-porn. It’s the instagram stories version of information.

You get a new insight everyday, you feel good about it, and then you forget it - because there’s no place in the brain to hang it. There’s nothing to connect it to. It’s creating just another data point, rather than knowledge.

One point I didn’t touch on in the information vs knowledge discussion is that information left on its own decays.

Hanging it requires thinking about where the idea is coming from, developing a framework, or installing it inside an existing framework. That takes a lot more effort - both, to create and consume.

The kind of content that resonates with me is one that explores some of these connections before I start thinking hard about it. This is another reason why I love Paul Graham’s writing: not only does he state a new idea with interesting analogies, but he also explores what it means for X, Y, Z, connecting it to all those things.

When I write now, I keep this in mind. I want to expand the ball of knowledge in several directions. Maybe one spike will stick into something you already know, and that helps hang this spike along with the ball into your mental framework. You’ll then remember this longer.

So, good content is more spiky. Things I can connect with. More spikes mean more chances for me to understand and hang the concept in my mind.

The more ways I can explore the topic, the better. The more senses I can engage, the better. The more mediums I can use, the better.15

This puts a natural barrier on the content size. Short form loses out to long form because you have limited opportunities to connect the thing you’re writing about to everything else. A quote image on Instagram is rarely dense. It’s hard to deliver all the implications and connections on where the quote came from, or how the author consumed two quotes, and produced this baby quote. I’d read a blogpost on quotes, if it can do this.

Distribution is key

In the end, even if no one reads this blog, it would suck a lot for a few days, but given the benefits it gives me, I’ll keep writing. That’s how I started, anyway. But, I’d prefer people read this, since having a community means better feedback loops and I learn more.

So, my motivations are purely selfish.

I want the right people to read this blog. It’s a way for me to attract people I have a higher probability of liking into my life. I have a hard time finding interesting friends in physical space (I’ve been very lucky with the friends I did find). I want you to poke holes in my arguments. I want to build an Idea Lab.

How do I make this happen?

I’m not a company, so following every distribution guide out there makes zero sense to me. Most of these strategies are about throwing lots of random crap on the wall and doing more of what sticks.

One, I don’t have that kind of manpower.

And two, I don’t want to throw random crap. Just crap I’m interested in, crap that makes me smarter, and crap I think will benefit others. Crap that isn’t crap to me.

I think quality over quantity is a better long term winning strategy. In a world of information overload, why will I want to bring more quantity in?

I’ll be slow in the beginning, but over time, with the consistent quality, I’d gain more friends and adversaries.

This goes against most conventional wisdom I’ve read about writing: quantity leads to quality. That’s probably true if my only goal were to improve my writing. Will it improve my thinking as well?

Challenging my own ideas

Thanks to the feedback loops in place, I now feel this uneasiness when I’m writing something unsubstantiated. It usually happens when I write things down, because that’s when I’m formulating the thoughts in concrete (or text).

Reddit was particularly brutal, once. I tried to pattern-match something that already came with a manual. Then I put a clickbaity name on top. Ugh.

While the content helped me learn quickly, it’s an incomplete (and mostly wrong) model of how Vim works. Now that I’m aware, I’m happy with this incomplete model: I don’t want to put in the effort to learn Vim properly.

But, everything else isn’t like Vim. This cautioned me to explore what I was writing, better.

A few more iterations with different posts, and the awareness of the shite thinking process awakened a second brain inside my head. This second brain looks over the first and critiques it. The two brains usually take different viewpoints, so I get multiple angles now. When they align, alarm bells ring. This is better.

My critiquing brain isn’t perfect yet, but it’s getting better with practice.

Cringe Posts

While we’re already cringing at that Reddit thread, here’s more to remind me not to become an insight-porn-attention-junkie creator or consumer.

Please join the dissection, it helps!

Starting with the first post ever, A Simplistic explanation to Mental Models.

I love the idea: Use a mental model (The Map is not the Territory) to explain what mental models are.

.. I try to keep it simple, and then start the heading with “Simplistic”. For fucks sake.

How to learn anything quickly: leverage the vocabulary - It’s a helpful idea, but it’s an optimization before understanding the platform. Wouldn’t work for anyone else.

How to hack your life like a video game - A poor attempt at explaining gamification.

How not to live life - fuck insight porn. Thankfully, I was conscious enough to not go all gung ho: “I’ll teach you the meaning of life, listen to moi.”

How to break through the trap of consumerism - trying to keep up writing a lot.

How to make plans with friends without feeling like shit - I think I’ll leave this one at the title.

It’s funny how most of these start with “How to”, because I read that’s what makes a good headline that gets lots of views on Medium 🤮16. Telling people how to do things after doing them once? Nice.

On this blog, I renamed “How to make plans with friends” to “Computational Kindness”. This probably was the first inkling of detaching myself from the Medium playbook.

At least, they are all in the early part of the year. Does something from the last 6 months disgust you?

Stats

Other posts were better. Some did well, and some I was proud of.

Overall, this blog received just north of 300,000 page views.

The blog made enough to sustain itself, which is an important goal for me.

Hosting costed $42 on AWS.

Domain and email costed $65 on GoDaddy.

The Amazon Affiliate programme made about $152, with shipped items revenue at $3,213. This was unexpected, but again, the world isn’t like me.

Carbon Ads made about $150 too.

Google Ads never paid up, but at the same time, Carbon Ads reached out to me, and I prefer their curated ads.

So, I removed all google ads. The website looks much cleaner this way, and I don’t think the ads are obtrusive anymore. I’ve set their opacity down to 50% as well, to prevent them from being “too bright”.17

Setting up as a wordpress site would be cheaper, but I don’t like wordpress. I like the flexibility of a static site generator. This also doubles as a great learning opportunity.

Fun Fact - Did you know that the social sharing images, title, and description - which show up on Twitter, Facebook, and Linkedin are derived from meta tags in the head of your HTML. I didn’t know this until I asked the question “Why can’t my website have pretty images on Twitter shares?”

Idea Muse

At the end of Q1, I started this newsletter. One idea every week.

It’s been golden. Every one of these ideas is designed to make you smarter. Either factual knowledge that helps navigating the world, or knowledge that helps think better and exposes a new way of thinking.

If you like it, consider signing up.

(Assume an annoying pop-up shows up now)18

How the human body works

This is one of my favourites from the Idea Muse.

Inspired by reading Leonardo Da Vinci, I asked my doctor-friend how can I dissect a human body and see what’s inside. She said it’s difficult. I could look at operation videos on youtube, but there’s lots of blood involved and the focus is on healing the patient, not exploring the insides.

Well, there must be dissection videos on youtube too, right?

Say hello to Dr. Gunther and his epic tv show.

Did you know there are blood vessels inside our bones? And when you make a claw with your hands, the “lines” that show up on the back aren’t bones, but tendons. Or that a muscle always connects two different bones. There will be no movement if it’s connected to the same bone. And finally, muscles only work in one direction, which is why you always need a corresponding pair on the other side to bring your bones back in position (e.g: biceps and triceps)

I wish bio classes in school were these videos instead of photos in a book I couldn’t imagine. Can you imagine how muscles look from those pictures?

Books I read

I read 40 books in 2019. My Goodreads has a nice visualizaion.

Looking forward

I’ve gotten great at information consumption. I love reading and I read almost whenever I can. It’s an epic habit to have.

However, I’ve realised I’m pretty shit at assimilating. My habits for converting information into knowledge are abysmal.

From time to time, I’d see the connection: what Morgan Housel says is exactly in sync with what Daniel Kahneman says! – and this is exactly what Charlie Munger says: build a curriculum for yourself, and ascribe the things you’re learning to the most fundamental discipline. If you don’t, you can’t keep up with things, learning snapshots instead of the general principles.

I usually just take the newest packaged information at face value, discarding the old ideas, or worse, not even remembering I had an old version in place. Sometimes I’ll have a faint recollection of reading something like that, but it will usually be lost in my notes.

It’s like trying to eat a marble. I’m not used to it. And sadly, digesting information isn’t something I learned at school.19

If I wanted to eat a marble, just swallowing it isn’t enough. My stomach would reject it, unable to break it down, so will the small intestines, where the nutrients are extracted. In the end, I’ll shit the exact same marble I ate.

How could I change this? Well, I’ll have to augment my stomach, or turn the marble into something consumable before it enters my mouth.

If I wanted to augment my stomach, I’ll probably need some tools. A laser-precision dissolver? My stomach becomes more powerful and can break the marble down.

If I wanted to turn the marble into something consumable, I’d probably hire a skilled marble digester to convert the marble into something I can digest. This is similar to how a momma bird chews the food before passing it to her baby bird.

I prefer a hybrid approach. The first option, for things I’m interested in. The second option, for things i’m not sure about yet.

To digest things myself, I need to figure out tools and habits that will help me do this well. I’ve just started down this path, with reading How to take Smart Notes, and I’m excited to see where things go with it. It’s a beautiful book, explaining why my existing platform has come up a bit short.

For the rest, I got to wait for all the momma birds to digest things themselves. But will consuming this work for me? I’m not sure yet.

So, next year is going to be about more consumption, and more synthesis.

Friendships

The other thing I want to focus on is making friends online.

Like I hinted at earlier, this is one of the biggest reasons for this blog to exist.

I dislike partying, and I suspect I have a higher chance of meeting the people I want to meet, online, rather than some deafening bar in Soho.

And, well, that’s it for this year. Email me. Sayonara.

Appendix: Doing your own annual review

My January 2019 monthly review, in full:

Okay, just the weekly one took a fuck tonne of time. This retro will grow slightly more slowly than the weekly. Since I don’t come to it that often -=> less chances to iterate over / more time taken to iterate.

But looking at the 75 new ideas I got last month - DAMN this is something 😄

(1) Indeed. And the quarterly would take a fuck tonne more time 😛 and will happen 0.25x times. I didn’t write much for Jan - because I wasn’t looking at the weekly then.

These three sentences are coloured with more than a few ideas from this annual review. The year was all about finding more instances, pattern-matching, and making it more precise. All I did was follow the hints from my observations.

The bit in (1) is when I do the next months review and revisit the old one to see if I have something to add.

Like I mentioned in the human log, starting with complexity is a failure mode. Start simple and watch it leave you desiring for more. Then, iterate. Add. It’s easier to do these reviews when you know you need every item on there. Copying someone elses rarely works out, because you aren’t sure what value asking that question gives you.

For example, the most powerful weekly review question I had was this: “What did I learn about me?”. It seems insignificant, but aggregated over the year, I found surprising patterns. I added this question in when – thanks to all the tracking I already had in place – I found out something interesting twice. “Oh, a pattern!”

Note: All book links are affiliate links.

-

For sufficiently long term projects. Hacks are great for short term gains. ↩

-

All book links are affiliate links. This is the first book link, so I’m putting a pointer here too. ↩

-

I haven’t practiced much deduction, lately. Except guessing the nationality of my matches on Tinder. ↩

-

I felt uncomfortable saying every gym session compounds. It feels linear to me. I either go to the gym or not, and every session makes me a little stronger(?). Every non-session makes me a little weaker(?). But then, depending on how I work out, not every session really makes me stronger. If I just do cardio, VO2-max may improve, but strength might not. So, whether it compounds depends a lot on what kind of workouts you are doing. ↩

-

Digital money, at least. ↩

-

Or, are they? I haven’t thought much about it. If you have ideas that suggest otherwise, I’d love to hear them. ↩

-

An iteration can be any measure of time or frequency. In this case, I’m taking one iteration to be one day, and the unit on the x-axis is thus in days. ↩

-

Desmos is this cool online graph calculator. I used that to build the graphs. ↩

-

The upside is limited too. Limited by physics. But it’s a high ceiling, and not one I worry about too often. ↩

-

Maybe a bit more if the human is big. ↩

-

It’s scary how many things are wrong with this paragraph. ↩

-

That’s probably true for lots of disciplines today, too? Shout out to Latin. ↩

-

Ergo, I need to go broad with my thinking and the disciplines I touch, too. Damn, I love writing. This is also why I tried to use graphs to explain compounding. It brings another dimension in, and now when you think about it, not only will you see the equation, but also the graph. ↩

-

Another fundamental realisation was that people who do read this kind of stuff aren’t the people I want to target. ↩

-

There’s an expanding brain meme opportunity here. Starting with a million ads on the website, to opacity 0.5, and ending with invisible ads. Haha, funny. ↩

-

Don’t worry, it won’t actually show up. Does saying it will, work just as well? I doubt it, but let’s find out. ↩

-

Note to future self - learn this well enough to teach my kids how to do this ↩

You might also like

- Agentic Debt

- What I learned about burnout and anxiety at 30

- How to setup duration based profiling in Sentry

- How to simulate a broken database connection for testing in Django