A Guide to Climate Change

What drives us to do great things? Purpose. It’s a fundamental need. If you’re a barista at Tesla, do you know how you’re accelerating the world’s transition to sustainable energy? We understand how important this is. We try to design companies around this. Simon Sineks life’s work is this. It’s surprising to me, then, that we don’t ask this question more often in one of the biggest problems we face today.

What’s your purpose in the fight against climate change?

If you’re wondering when you signed up to fix this problem, you were enlisted the moment you were born. Of course, that doesn’t mean your role can’t be that of a detractor. I hope it isn’t, and if it is, I want to show you how that fits in, too.

If you’re unsure of your purpose, or want to find out where and how everyone else fits in, this guide is for you.

By the end of this guide, I hope to provide three things:

- A model for how we can stop climate change

- Where do you and I fit in, or our purpose

- What we can do about it today

There’s some speculation involved. Somethings might not turn out like I imagine. We might even end up destroying Earth. A meta-goal of this guide is to become a self-fulfilling prophecy. The more people find value in this model, the closer it comes to reality.

Let’s start with the problem. We will figure out a few principles to model the solution on, then come up with a model for change, and then choose which part we want to accelerate.

The Problem

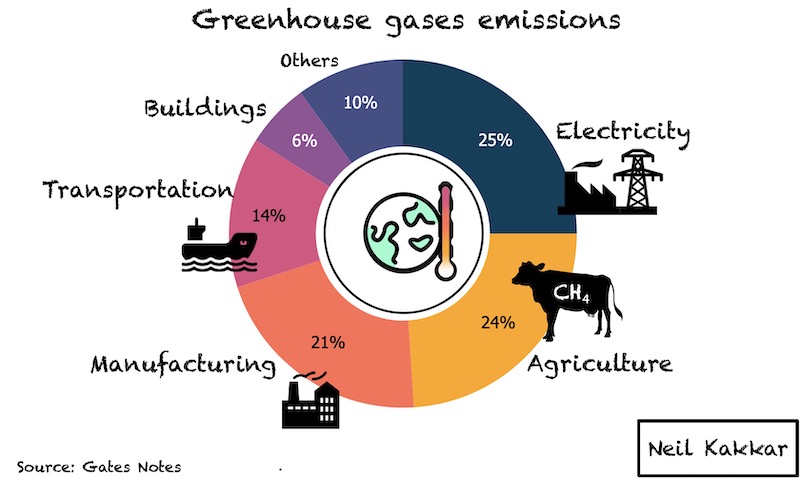

Greenhouse emissions aren’t just about electricity and fossil fuels. There’s so much more to it. The way we produce electricity is 25% of the problem. The remaining 75%? Agriculture, manufacturing, transportation, air conditioning in buildings and a few more small sources. Stopping climate change means attacking all of them, not just electricity.

That means taking on McDonalds, every butcher and beef farm in the world, and Shell, Total, BP, Exxon, and all other oil, natural gas and coal mining companies, electric distribution companies like EDF, Enel, and also every construction company, every concrete producer, and every industry that depends on them. More than that, it means winning.1

If that’s not worrying enough, we are also going against human nature.

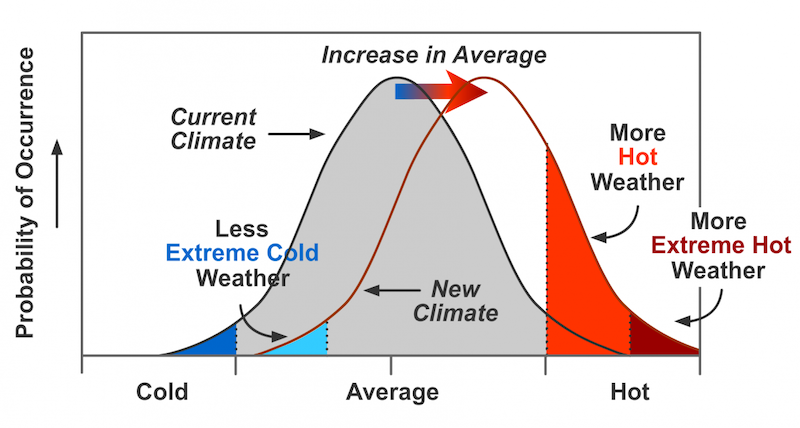

Without getting to net zero emissions by 2050, we’ll be on track to raise the global average by 2 degrees celsius. This may not sound like much, but that’s the tyranny of the average - it hides the extremes. When the entire temperature bell curve moves to the right, those on the extreme ends find deadly heat waves and melting ice sheets. At just 2 degrees, the entire coral reefs of the world will die, leading to a massive disruption of the ocean ecosystem.

Remember the wolves? These Trophic cascades will affect the entire world, and we aren’t sure how. It’s a complex adaptive system, and we are pushing it past its breaking point.

There is no external enemy. There’s no asteroid coming at us, There’s no expanding sun yet, forcing all nations to work together. We are the enemy. It’s difficult to get fired up for a cause when you’re on the wrong side of it.

Before we get to the nitty gritty of how to stop this change, let’s build up intuition for what climate change is and how it occurs.

Intuition for Climate Change

There are 3 main principles.

First principle: Greenhouse gases trap heat on Earth and make it warmer. These include CO2, CH4, N2O: Carbon dioxide, Methane, Nitrous oxide, and a few others.

Second principle: The more greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, the faster Earth heats up.

Third principle: The higher the rate of greenhouse gas emissions, the more they accumulate in the atmosphere.

Right now, we are at net positive emissions. Every year, we add more CO2 to the atmosphere. Even if we reach net zero emissions by 2050, we’ll keep adding more greenhouse gases to the atmosphere for 30 years. Thus, we’ll keep increasing the rate of heating. Even in 2050, the planet will continue heating up - faster than today, but at net zero, the rate will stabilise.

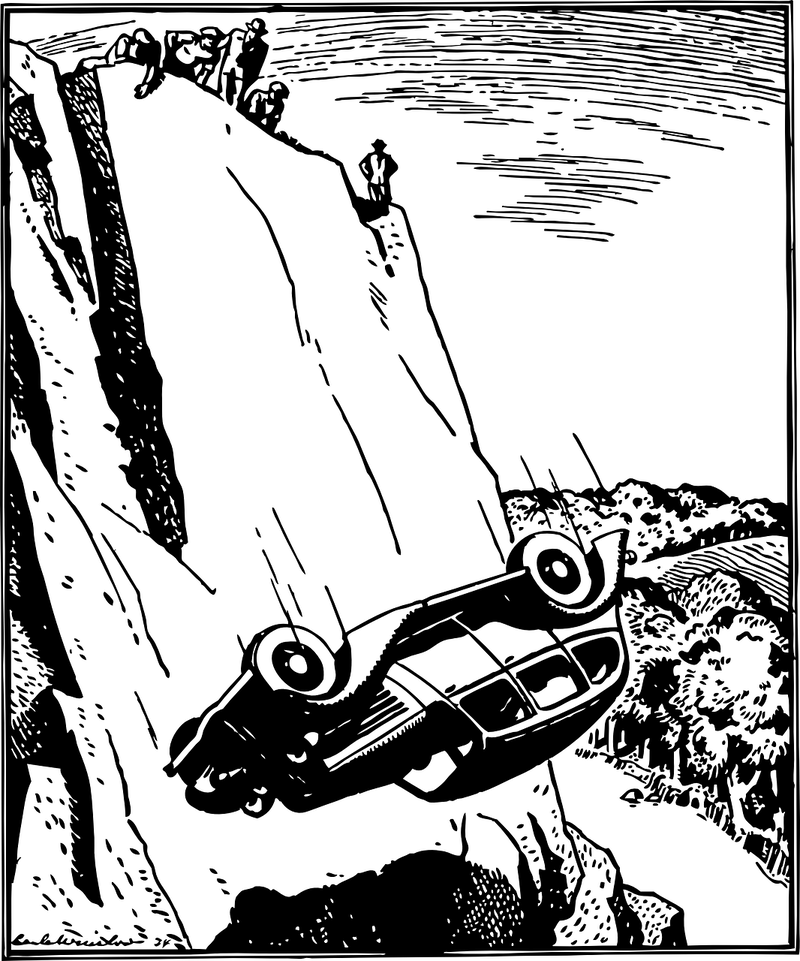

Imagine a car on a super long path2 that ends in a cliff. We are pushing this car harder and harder, which makes the car keep going faster and faster. We will continue pushing for 30 years, and when we stop, the car will continue going at its current speed. This roughly translates to the car falling off the cliff. It doesn’t matter how long the path is, we will get to the cliff.

What we also need is a method to brake the car so we can slow it down after we stop pushing. In greenhouse gases terms, this means negative emissions. We’ll need to reduce the total amount of greenhouse gases in the air.

The consequences of failure are severe. Droughts, floods, displacement of people, less available land for growing food, starvation, and a lot more covered in great detail on the internet.

So, what can we do about climate change?

Extraordinary problems require extraordinary solutions. In complex adaptive systems like the real world, this translates to strong feedback loops driving momentum towards the right goal: political and economic acceptance that climate change is real, and an extinction-level crisis.

Learn from the past

Before designing our feedback loops, we ought to learn where we succeeded and failed in the past. There are 2 prime examples we can learn from.

- Montreal Protocol, or the fight against the Ozone Hole.

- The failure to stop climate change in the 1980s.

The Montreal Protocol is probably the most effective global initiative ever. Every nation in the world came together to combat a common enemy: The ozone hole.

This fight began with scientists discovering the “hole”. It wasn’t a hole, just an area of lower ozone density, which appeared like a hole in images. This characterisation was important as it got the media’s attention. The newspapers published front page articles about Armageddon descending from above. This alerted people, who panicked and demanded action by their governments.

Companies like DuPont manufactured CFCs, the cause for the hole, and they faced the heat too. Afterall, a ban on CFCs would mean an arm of their company chopped off. With mounting pressure and continued media attention, they realised an alternative. They could create replacement chemicals and profit. The flywheel started spinning as they aligned with the people and forced policy makers to ban CFCs. Today, we are on track to “close” the ozone hole completely.

The failure to stop climate change in the 1980s displays the other side of the story.

The scientists brought climate change to the attention of the government and the media. It wasn’t a spicy enough story to warrant page 1 coverage. “We might face adverse conditions by 2100 if we can’t curb the global average rise in temperature to 2 degrees by 2050.” The policy makers held a few discussions every year. But without consensus, there was no action.

Exxon didn’t care about how much the world would warm, only how much it could be blamed for.

Exxon, an oil and gas company considered responsible for global warming launched a few studies of its own. It didn’t care about how much the world would warm, only how much it could be blamed for.

The detractors amplified the problem. “Changing Climate” was a research report stating that “the general consensus is that society has sufficient time to technologically adapt to a CO2 greenhouse effect.” This motivated Exxon to revise it’s position too. It claimed what they were doing wasn’t a problem anymore, as stated in “Changing Climate”.

It wasn’t a political problem, either. Why make policy decisions over something that might not happen 10 years from now? Why set yourself up for re-election failure when no-one important cared about it?

David Slade, the director of the Energy Department’s carbon-dioxide program, considered the delay in cause and effect a saving grace. If changes did not occur for a decade or more, he said, the policy makers in the room couldn’t be blamed for failing to prevent them.

If changes don’t occur for a decade or more, people in the room can’t be blamed for failing to prevent them. So what’s the problem?

We don’t have a big bad enemy this time around. We are the enemy, which is a difficult pill to swallow.

There’s no local optimum, only a global optimum

One city going emission-free is a great precedent for other cities to follow. However, just one city doing this isn’t good enough - they share the air with neighbouring cities3 and as long as the total emissions in the world are rising, we are at risk.

If you push the car with one hand instead of two, it might go a bit slower, but without the brakes it will still go off the cliff.

For example, China trying to control the rain during the Beijing Olympics caused tensions among neighbouring countries. It modified not just the weather in China, but neighbouring countries as well.

In such a case, all our measures need to go all-out. It’s not enough to power just the Scandinavian countries by 100% renewables and 100% anti-beef. What about the rest of the world?

When you want to go against human nature - the short term thinking and the selfish behaviour - half-assed reforms won’t do. What we need are feedback loops that reinforce decisions and move us towards a better future automatically. Situations that don’t give ourselves the chance to think short term.

This involves getting the people, the enterprises, the bad actors, and the governments, all aligned to the same vision.

The more actors aligned, the easier it gets to coordinate global initiatives. The fewer aligned, leads to infighting and conflict before reaching the international stage. (Hint: That’s USA today)

As Melinda Gates put in her 2019 Annual Letter with Bill Gates: “There is nothing about putting your country first that requires turning your back on the rest of the world. If anything, the opposite is true.”

Strengthening health systems overseas decreases the chance of a deadly pathogen like Ebola becoming a global epidemic. And ensuring that every parent everywhere has the opportunity to raise safe, educated, healthy kids makes it less likely that they will embark on desperate journeys to seek better lives elsewhere.

And getting people aligned to the vision starts by building awareness.

Building awareness

What happens if this year the temperatures were cooler than usual?

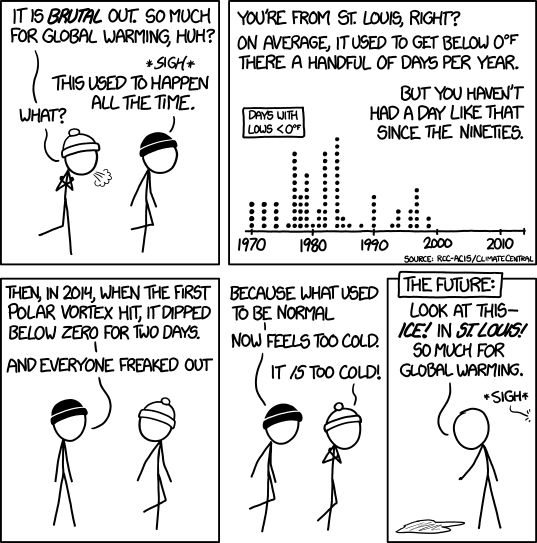

Like the dinner guest who says that smoking doesn’t really kill, because some great-grandfather and grandmother of his smoked and lived to 110. Similarly, Trump and others think that global warming is fake because the weather today, or this year was colder. Scientists explain why that’s wrong.

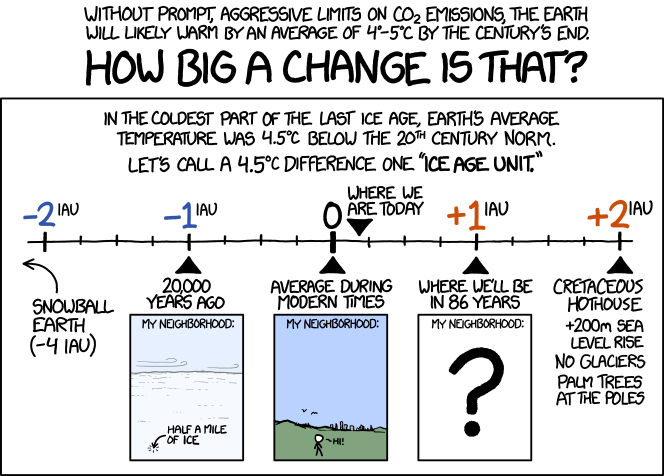

So does Randall Munroe:

I could argue for global warming using the same method: July 2019 has been the hottest month in the history of the world. But, that will be me falling for the exact same fallacy as people professing climate change is fake.

The real measure is the aggregate. The global averages have been rising. The temperature cycles through hot and cold seasons, with small delays - a bit extra CO2 released today doesn’t immediately increase the temperature tomorrow.

And boy, we can’t handle delays. An ancient mobile phone taking 3 seconds per tap boils our brains. If you’ve ever been in a shower with different taps for hot and cold water, you know how this is. Too hot? Increase the cold flow. Oh, nothing happened? Keep increasing, keep increasing. Oh perfec–! Argh, why didn’t it stay there! It’s too cold now! Increase hot water?

When feedback is delayed, our instinct is to continue “fixing”, which usually leads to an overcompensation. It’s the same idea with oversteering while driving.

With climate change, we only have to worry about the too-hot side. We probably won’t be able to open the cold-faucet, barring some amazing innovation. All our focus now ought to be on reducing the hot-water-tap as much as we can.

Another misconception to tackle is that reducing emissions is going to hurt economic and social growth, which is the prime measure on which politicians are judged today. Given all the co-benefits that come with reducing emissions, the net cost might become zero.

Co-benefits such as reducing deaths from air pollution and boosting technological innovation may lower the net costs of climate action to zero or even lead to a net economic benefit rather than a cost, studies show. There are entire organisations dedicated to researching and promoting this research.

When it comes to generating awareness, we are in a sweet spot today. It isn’t the government, or just a few powerful companies that control the media. Thanks to our social platforms, everyone can have a voice and reach a lot of people - climate change activists and detractors alike.

One good way to learn about building awareness is the 2016 US Elections, as Russia allegedly managed to sway them. Can we rope in our biggest tech companies to take sides in this emergency? A mandatory “climate change is real” ad everywhere on the internet? Random facts about what causes climate change? Random facts about what we can do everyday to help? Can we leverage our aligned political leaders to curb the backlash? Maybe legislate for companies to promote the right message? 4

Now, let’s get into specific causes - afterall just saying people need to be aware isn’t enough. I got to put everything together in an easy to consume package, too!

Things to be aware of - Trees

Trees, or forests, are great. They are a natural braking system for our metaphorical car.

Via a process called carbon sequestration, they remove CO2 from the air. Photosynthesis takes in carbon dioxide and sunlight, stores the carbon in the bark, leaves, and roots (as cellulose) and gives out O2.

Planting trees seems to be the most straightforward way to combat climate change. However, we might be heading in the wrong direction - with rampant deforestation, especially in Brazil.

The overwhelming direct cause of deforestation is agriculture.5 We clear out forests to make space to grow crops and create grazing grounds for cattle.

There’s a small benefit to grasslands over forests though. The lighter grasslands increase albedo, or the reflection potential of that area of Earth. Lighter areas reflect back more of the heat. However, right now, with the high CO2 levels, forests win. The net effect is, forests are good, grasslands bad.

The worst bit? When we burn wood (trees), we release all the CO2 they captured throughout their entire lifetime back into the air.

The Wikipedia page has more information.

Things to be aware of - Beef

How does me eating beef today result in a hotter Earth tomorrow? This makes no freaking sense!

That was my first reaction, too. It’s an involved process.

Remember how forests are good, grasslands are bad? Cattle requires grasslands. Mass-produced grain-fed cattle need space, as well as grains. Thus, deforestation. That’s strike one: The process of creating meat leads to deforestation.

Then, come the cows themselves. They fart. A lot. One cow might not make much of a difference, but the 1.5 billion cows farting everyday is a lot. All this farting releases lots of methane into the air, which is a greenhouse gas. That’s strike two.

Strike three? There’s none yet, but I think plant based meats will be strike 3. They don’t fart, and don’t require clearing out large areas of land.

I mention beef and cows everywhere, but the same is true for all cattle: cows as well as sheep, buffalo and goats.

Grass-fed beef may be different. I haven’t done enough research to write about it. There’s evidence on both sides

Things to be aware of - Transport

One car, one person vs one full airplane travelling the same distance. What causes more emissions per person?

In this case, it’s the car. But get more people in the car, and your emissions per person plummet. Further, we have alternatives to cars running on petroleum or diesel: electric cars.

Electric cars reduce the footprint to almost zero, provided the electricity is green.

What’s worrying is that there’s no alternative yet to ships and planes

And on the whole, ships and planes account for 50% of transport emissions. Cars share will shrink more, but we have no gameplan for planes and ships.

But, let’s back up for a second. How exactly do cars, airplanes and ships pollute? It’s the internal combustion engine. We burn fuels like diesel, petroleum, compressed natural gas(CNG), in the engine, which release CO2 and other pollutants.

Things to be aware of - Concrete

Our buildings need concrete, and producing concrete releases CO2.

Things to be aware of - Carbon Footprint

The carbon footprint is a measure of total emissions of a person, an object (like airplanes), or a company.

Things to be aware of - Carbon Offsets

Imagine going to a restaurant and seeing that lovely lasagne on the menu. Looks soo good! You decide to order the lasagne and tell yourself, you’ll work it off by doing extra at the gym tomorrow.

What you just did was an energy offset. You consumed a pleasurable source of energy and worked to get rid of it in another way.

Carbon offsets are the same. For things you need and don’t have renewable alternatives (like airplanes), you can offset your emissions by paying a company to plant trees, funding solar research, or something similar.

Here’s a guide for offsetting flights.

That’s all for awareness today, let’s move on with our feedback loop.

Awareness fights against short term thinking for action.

Long term thinking requires a concerted effort

Short term thinking is an evolutionary instinct.

People trying to get food on the table tomorrow don’t give a damn about climate change 10 years from now. We can’t stop these people burning wood for fuel. Not unless we have an alternative. There’s no moral high ground here - morality doesn’t come into the picture unless your basic needs are met.

It’s partly cultural, partly human nature. And given our human nature has focused on short term results and hyperbolic discounting, we have designed (or evolved) our culture to reinforce that. Businesses move in quarterly cycles and earnings. Policy makers focus on 4 year terms.

Some people and organisations get it. They engineer themselves to go long. They build a culture around long-term benefits. They flourish.

A big part of fostering long term thinking is getting the incentives right. If it’s ingrained in the culture, even better.

Incentives

For the not-so-average person who understands and can think somewhat long term, awareness suffices. “If we don’t do something about climate change, we might die, and our children definitely will die.” That’s a pretty strong incentive to do something about it.

Things get tricky when we get to companies and governments, which are detached from the people who work there. For them, the directive, like human beings, is to survive and prosper. The catch? Survive and prosper as long as I, the leader, am in power. This is usually 4 years in government, and for companies, can be up to 10 years.

It’s the high stakes version of “Let me watch just one more episode on Netflix, then I’ll sleep, promise.” Even though it will mess up the entire day tomorrow, I’ll get the satisfaction of figuring out what Tommy Shelby does next, or how Ashirogi Mutou improve their craft.

Most policymakers today will be dead by the time we feel the effects of their climate change policies.

It’s a short term vision, because that’s what the current incentives promote.

In Politics, our 4/5 year political cycles aren’t enough to stop climate change. We’ve learned this from our failure in the 1980s. Problems on a 10 year time scale are problems for the next leader. Then it becomes a “10 year timescale” for the next leader, too. We keep extending this because there’s no hard 10 year rule. Temperatures are already up 1 degree from pre-industrial levels. We’ve somewhat acclimatized. We are like the boiling frog.

The Boiling Frog: If a frog is put suddenly into boiling water, it will jump out, but if the frog is put in tepid water which is then brought to a boil slowly, it will not perceive the danger and will be cooked to death.

In psychology terms, that’s contrast bias.

The same problem exists with companies. Quarterly goals hinder long-term progress. Amazon evaded this trap by not being dependent on the shareholders (it pulled them into the vision instead). They expanded. They had enough autonomy and shareholder support to go 10 years straight with no real profits. “Amazon and Its Admirers Shrug Off Report of a Loss as Sales Keep Climbing”

Their metric was separate from the markets and common investors. It wasn’t how much profit we can show this quarter, but how much more market share can we capture. We know we can profit when the time comes.

Similarly, we have metrics that track global warming: The amount of CO2, Methane and Nitrous oxides in the air. Do not talk in terms of hot and cold weather, but how much CO2 are you removing from the atmosphere. The temperature stabilization will follow when the time comes.6 This is exactly what companies do, too. In systems with delayed output, the next best thing to measure is the quality of the inputs. We can’t judge how much revenue this person generated, so instead, we figure out how hard they worked everyday.

In systems with delayed output, the next best thing to measure is the quality of the inputs.

And these are the metrics we ought to judge our political and company leaders by.

For companies, there’s the Task Force for Climate Related Financial Disclosures, or the TCFD. It urges companies to disclose their emissions as well as the risks involved in not driving towards a sustainable future. The thesis is brilliant: If the company isn’t sustainable, chances it will survive will dwindle as we move to a sustainable-first world. This drops the share prices, and in turn incentivises companies to become sustainable.

It’s a different story with company leaders who have enough autonomy to direct their entire organisation. If these leaders care about climate change, they can move their companies in the right direction. Two prime examples are Bill Gates and Michael Bloomberg.

For policy makers, this role falls to the media and us, as individual citizens. Theoretically, they are our representatives. They represent our wishes. They have the most power to design incentives for companies and utilities that raise emissions: Using the law, and economic policies.

Policies work in two ways: subsidies and taxes.

Subsidies are the carrot - they decrease the cost of something7

Taxes are the stick - they increase the cost of something.

A subsidy of 10$ per barrel on oil means that for every barrel a company sells for 100$, the customer only pays 90$ and the 10$ comes from the government. This encourages consumption of oil, as it’s relatively cheap for the consumer. Where does the government get this money from? Taxes!

Just like income tax, there are taxes on certain goods. A 10% tax (or duty) on a barrel of oil means that for a 100$ barrel, the consumer has to pay 110$. This discourages consumption, as the barrel gets more expensive.

If you’re thinking this isn’t significant - plastic bag usage in the UK dropped 86% when the cost rose from 0 to 5 pence (6 cents).8

Right now, we have subsidies of over $1 trillion for fossil fuels. This is insane. No wonder it promotes behaviour in the wrong direction?

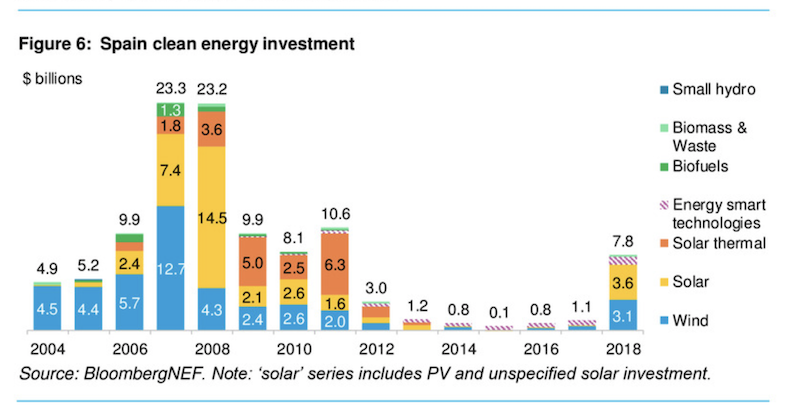

At the same time, there are some subsidies for renewable energy like solar and wind too. Subsidies help a lot. Consider Spain. In the early 2000s, with subsidies for renewables in place, renewable plants installations thrived. With the decision to cut all subsidies, renewable investments declined. As renewable subsidies are coming back to Spain, the investments are increasing again.

A page from the 2019 Spain Policy Outlook report, BloombergNEF

Why are we subsidizing fossil fuels? They ought to be taxed. Makes sense right? Tax what you want to punish, subsidize what you want to promote. If that’s not happening, it’s probably because it’s not what people want, or the wrong leaders are elected, or the companies with vested interest hold too much political power, or what you want is in the minority. That’s again why awareness is so important.

If there’s no change, then as Robinson Meyer put it, people will continue to “subsidize air pollution with their life.”

350.org is one organisation working to fix this. Their tenets:

- A Fast & Just Transition to 100% Renewable Energy for All

- No New Fossil Fuel Projects Anywhere.

- Not a Penny more for Dirty Energy

The iron law of markets is that if renewables become consistently cheaper and more dependable than fossil fuels, the entire world will move towards them. We can do this by making fossil fuels more expensive via carbon taxes, or making renewables cheaper via innovation and subsidies.

These incentives are ones that come from the supply side. Every tax, be it a carbon, beef, or a deforestation tax attacks this side. Same for subsidies.

Then, there’s consumers on the demand side (you and I). Aware citizens boycott dirty fuels and dirty meat. Aware citizens demand their companies to do the same. Aware citizens stop contracting with companies that aren’t sustainable. Aware company leaders direct their companies to do the same. It’s renormalization on the global scale.

The million dollar question though: How do you rope in oil and gas companies?

Taking a page from history, we want to pull off a DuPont. We need alternatives or a transition sequence. This is where innovation comes in.

Fostering Innovation

Not only do we need to get to net zero, but we need to go negative: Removing greenhouse gases from the atmosphere. Incentives to foster innovation will help with the transition plus create new kinds of brakes to stop our car from falling off the cliff.

Innovations need money though.

Private money is easier: All you need is one wealthy person who believes in saving the world. This is how Bill Gates decided to fight climate change, via The Bill Gates foundation.

Public money is tougher: You need leaders to assign a big enough budget for innovations. This won’t happen if they believe the problem is a hoax. We still want public money though - it’s an order of magnitude greater than private money.

It’s like we’re going to space again. Funding NASA brought about 2,000 other innovations like LASIK, ear implants and artificial limbs. What’s the climate change fight going to uncover?

Innovations in renewables

This is probably where we’re doing the best. The cheaper and more efficient solar and wind get, the more people adopt them. There are a host of other problems to solve though.

- How would electricity distribution work? The current grid is designed with a stable output coal or gas plant in mind - no fluctuations with sunlight or the wind.

- With variable generation, we need batteries to store energy. We need a lot of batteries. There are some interesting storage mechanisms around, like pumping water up to high ground in times of excess electricity and letting it flow down and power a turbine in times of electricity shortage. The first time I heard about this blew my mind away. The energy generation part is standard, that’s how all dams work. But creating “artificial dams” as a battery? Damn, I love science!

- Is Hydrogen feasible as a fuel?

- Do we have backup sources for wind and solar during extended periods of cloudy weather?

What about the incumbent oil and gas companies? If it becomes clear to every oil and gas company that there exists a future without them, they know they’ll need to figure this out. Where do they have the advantage? Expertise in energy distribution and management. I think they’ll make great green companies, too. All they’ve got to do first is invest all their money into a green pivot. If we can show them that they’ll die without this, the benefits outweigh the risks.

This calls for transitional innovations, like CCS, or carbon capture and storage. Instead of switching directly to renewables, innovations like these aim to reduce the impact of coal and gas plants, by filtering out all carbon being emitted, keeping it in solid form. (Just like Carbon Sequestration in trees)

Innovations in meat

Lab grown alternatives, like Beyond Meat and Impossible Foods are a big thing because it’s a win for the environment. No cows for beef means no excess methane nor deforestation to create grazing grounds. How can we leverage this innovation better? How can we make it safe for everyone?9

Innovations in nuclear

Nuclear feels like the big bad enemy, because of Chernobyl, Fukushima and a few others. Compared to driving, the idea of a shiny green fuel killing us does seem more dangerous. According to the numbers, it isn’t though. And given the energy generation potential, it’s probably a major component to becoming a Type 2 civilization.

Like most ideas in this guide, we look back in history to learn our lessons. What’s happening with Nuclear has happened before. Daniel Kahneman observed the effect with Alar, a chemical compound not as dangerous as people made it to be in the 1900s.

“The Alar tale illustrates a basic limitation in the ability of our mind to deal with small risks: we either ignore them altogether or give them far too much weight—nothing in between.” - Daniel Kahneman, “Thinking, Fast and Slow.” 10

You can guess which side nuclear energy falls on.

Geo-engineering

I consider geo-engineering the backup option. The idea is, just like in the movie Geostorm, we control the climate to make it not too hot, nor too cold. I have no idea, yet, how this would work without consequences in neighbouring areas.

Sustainable processes

Sustainable symbiotic processes, like the Mulberry Dyke Fish Pond popularised in China, are processes that don’t deplete the Earth, and may end up enriching it.

The idea is simple: X needs Y, which needs Z, which needs X. If you can create this cycle, you have mini-loops feeding on themselves, and you get a potentially infinite source of resources.

Can we innovate similarly for sustainable processes that replace our current high-emission processes? I think hybrid cars would somewhat fall in this category.11

Bioplastics and material innovation

Remember we still have to tackle concrete? Say hello to bioplastics and new composite materials. They may prove to be stronger and cheaper than concrete.

All these ideas (and 100s more I haven’t written about) require smart people like you and I, as well as funding to find a solution.

Want a bigger list of the most impactful ideas ranked in order? Drawdown: The Most Comprehensive Plan Ever Proposed to Reverse Global Warming 10 is the book to get!

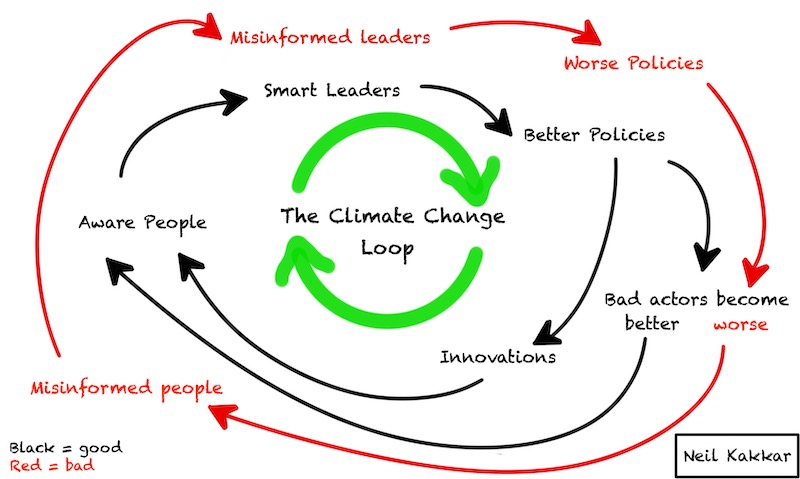

The feedback loop

With all these components in mind, our feedback loop comes together. We build awareness, which elects political leaders aligned with the fight, who foster green innovation and drive more awareness, and pass laws that make it hard for companies and people to thrive while polluting. Given the awareness, we judge these leaders over a longer term, with meaningful metrics, like % reduction in emissions. The policies to drive more awareness get more people aligned to the cause, which stabilises the leaders in power, as long as they are working towards the goal. We stop falling for party tricks like “a cold-winter is proof of no global warming” and do our part for the world, too.

At the same time, the detractors fund their own research about how climate change is fake. Driven by profit, some companies with vested interest in oil and gas may do the same. And they, too, shall try and convert people to their side. Don’t believe in climate change, here drive this new car, it’s a sweet guzzler.

Like most competing feedback loops, the one that hits activation energy12 first, wins.

However, these loops are still confined to the country level. Remember, we’re gearing for the global optimum.

This is where the Paris Agreement comes in. It’s a measurement of who’s in front, and who’s last on the emissions scale. It’s a global leaderboard. Taking a page from school classrooms and social networks: We are status-seeking, and want to rank first on the leaderboards. So do we as countries.

The agreement turns this into a competition. All it asks is for countries to report their emissions, similar to the TCFD. Once we have this leaderboard, we can do lots of interesting things, like penalizing countries not doing anything about their emissions, and helping out countries that need support.

How would you penalize a country? It’s not like we have a classroom teacher to punish them. What we do have, though, is interdependence between countries. Countries don’t go to war so frequently anymore because the profits of trade far exceed the costs of war. That’s a hint to where it will hurt: sanctions, and stopping people migrating.

It’s like being in a high school full of teenagers, with the most popular teens being the ones with the lowest emissions (no pun intended). But, that’s a while away. Having a few bullies with high emissions certainly doesn’t help.

On the whole, that’s a small way how we get to change the world.

Here’s what the loop looks like.

This loop needs some % of people aligned to climate change before it can start spinning. This is my purpose in this fight. To kindle the loop. And, your chance to choose what role you want to play. We’ve explored all the components of this loop, and you can choose one, or more positions in it.

Our purpose

The most important part is reaching critical mass - building up enough energy to reach activation. I don’t know the exact number, but there’s no harm in overshooting it. Oh, how I wish we could overshoot the number of people aware about the urgency of climate change. The Extinction Rebellion, a socio-political movement that fits this model well - considers the activation energy as involvement of 3.5% of the population. That’s about 2 million people in the UK. Can we reach it?

With this guide, you know more about the current state of things than the average person.13

You know how eating mass-produced beef “causes” climate change.

You know how cars and airplanes pollute. You know that we don’t have a clean energy alternative in sight for airplanes and ships.

You know we are still pushing our metaphorical car faster, when we ought to start braking.

You know now what it will take to get there.

It sounds almost impossible. Getting the entire world to agree on something? It alarmed me enough to spend a month just writing this guide.

Everything you do affects this feedback loop. That’s the essence of the feedback. It changes as you change.

When you don’t tell your friend about how beef is bad for the environment, you’re removing one extra obstacle from the demand side, which lets the beef industry thrive a bit longer.

When you vote for someone who doesn’t care about the environment, you’re telling the world it’s okay in my country, or my state. You’re falling for the short term game, and hindering the world to move towards a sustainable future.

Given enough small steps, we can get to a future none of us can imagine, because we can’t imagine compounding. We end up over-estimating in the short term and under-estimating in the long term. Perhaps that’s why the long term goal sounds almost impossible to me, while the things I can do today seem possible!

And of course, personal behaviour isn’t all we need to change. We can do more. We can insert ourselves into any part of the loop and accelerate it further.

An engineer? Get into the innovation space. See how you can innovate?

A psychologist? How can you get people with deep seated anti-climate beliefs aligned to the cause?

A CEO? How can you direct your company to be more sustainable?

Is this asking for too much? Maybe you can help us reach activation energy - and share this guide!

This might be a common civilization test before The Great Filter. Are we the first ones here, or did civilizations on other planets already destroy themselves? It’s the grand balancing act. When your species is too small to affect the globe, or lacking enough autonomy to go against basic instincts, short term thinking prevails. These guys blow the rest out of the park. They keep growing, and if all goes well, they reach a stage where they are on top of the food chain, just like us humans. Then, this species reaches a tipping point where short term actions leave the entire globe worse-off. But it worked for millions of years before hand. Would this species have the courage to switch?

I hope we do.

Remember, the 2 degrees is a lot.

This is the end of the guide. Next up is an interactive list. These are some ideas worth tackling. Do you have an idea? Email or tweet (to?) me, I’ll add it to this list!

Unexplored ideas to tackle

-

Make fossil fuels free. Is it possible to make the cost of fossil fuels free? Not via subsidy, but banning them from trade? If I can obtain fuels for free, (and nobody is paying) there’s zero incentive for any oil and gas company to go through the trouble of extracting it. Does this even work in free markets?

-

Leapfrog zero infrastructure areas. In places with no energy infrastructure, we have an opportunity to leapfrog, leaving coal and oil collecting dust… as fossils. What happened in China with mobile phones, can happen in Africa with energy infrastructure? While the west moved from desktops to laptops to mobile phones, by the time laptops got to China, powerful phones were already available. And China leveraged that. to make a quick jump. Can we do the same for energy infrastructure in zero infrastructure areas? Can we learn from the Scandinavian countries?

-

Carbon Sequestration in trees to inspire tech innovations to move carbon out of the environment.

-

Can we re-engineer the algae that initially formed the Earth’s atmosphere? There only used to be CO2. These microbes turned it into 21% oxygen, causing the oxygen holocaust, or their own death. On wikipedia: The Great Oxidation Event

-

Nuclear as a source of energy for planes and ships. Can we get nuclear efficient and small enough to fit on an airplane?

-

Molten Salt Fusion Reactors, please? Here’s why.

Epilogue

I struggled with this model because it’s not 100% accurate. Inner me screamed a lot at times, saying I’m simplifying this too much! I can’t just expect the right leaders to fix everything, and for everyone to elect the right leaders, and for everyone to even come together. Nor is it guaranteed that awareness suffices. Would you prefer a new car today or an extra year at the end of your life that you may or may not have? Despite all this, and my repeated emphasis of the difficulty, I think the model is useful.14 It’s a framework on which to lay everything we see happening and where we are lagging in the battle for climate change.

Here’s one example where I struggled to prove it will work. One incentive is to raise taxes on beef. There’s going to be backlash from everyone that wants to eat beef and doesn’t care about the alternatives. Leaders lose support of everyone in this category. A new leader rises. They say, “I’ll give you beef. It won’t be taxed extra.”

Who will win? - Depends on how many people still want to devour beef.

If you’d like to dive deeper, and get a more concrete analysis of the solution, check out IPCCs special report

If you’re in technology and looking for a dive into what you can do about climate change, here’s Bret Victor’s essay for technologists.

And if you want to know the least time consuming highest impact action you can do, it’s to share this guide.

Thanks to Anya Pearse, Nishit Asnani and Vanshika Bagdy for reading drafts of this guide.

-

Thankfully, we don’t have to take them all head on. We can get them on our side instead. ↩

-

Frictionless, if you will. ↩

-

And the rest of the world, eventually. ↩

-

There might be some concerns about this crossing the schelling point and down a slippery slope. That doesn’t need to be the case. It can be a special “class” of international issues which 95% countries agree on. ↩

-

UNFCCC (2007). “Investment and financial flows to address climate change” (PDF). pg. 81. ↩

-

And being mindful of Goodhart’s law. “When a measure becomes a target, it stops being a good measure.” I don’t know how we might end up reducing greenhouse gases and at the same time increasing global warming, but I probably just lack imagination. ↩

-

For the consumers. ↩

-

Although, you could argue that this is an infinite percent increase, hence a bad example. ↩

-

Some people aren’t convinced of the health benefits. ↩

-

Although, a transitory innovation seems more appropriate for hybrid cars. ↩

-

Or, as Jim Collins likes to call it, The Flywheel Effect. ↩

-

For now. Next year, maybe everyone knows this? ↩

-

All models are wrong, some are useful. ↩

You might also like

- If Sapiens were a blog post

- How To Understand Systems

- Psychology of Human Misjudgment

- The Personality Loop