All Stories Are Wrong, but Some Are Useful

Stories, not people, rule our world. We’re always telling ourselves a story about how the world works, and this makes stories very powerful.

For example, consider this story:

An American couple crash their car, die, and ascend to Heaven. God meets them, and they ask “What were the real results of the 2020 election, and who was behind the fraud?”

God says, “There was no fraud, my children. Biden won fair and square.” After a few seconds of stunned silence, the husband turns to the wife and whispers, “This goes higher up than we thought.”

Why does the couple’s political belief supercede God?

Somewhere down the line, what was an entertaining story became something people believed in. This matters because the stories we tell ourselves change how we view the world.

The unreasonable impact of stories confused me. How can a story have so much power?! For the past year, I’ve explored this question, and stumbled upon some surprising connections.

This post explores these connections and what they mean for you: from how stories create beliefs, to lessons from master storytellers about what to be wary of, ending with four powerful stories that have shaped humanity.

Along the way, we’ll also figure out why our couple in Heaven think as they do.

The Belief-Hypothesis Spectrum of Stories

Consider two stories. Story One is about the economy - how we’re doing great, or not so great, this year. Story Two is about Alice, a rabbit, and a rabbithole.

Which story are you more likely to believe?

Ask young kids, and they’ll probably connect with Alice and the rabbit. The economy? That’s too abstract - sounds like someone created it out of thin air.

While you might believe the story of the economy more, little kids might believe the story of Alice in Wonderland more.

So, we believe in some stories more than others. This degree of belief changes the nature of stories so much so that each kind of story has its own name:

- Stories we believe in are beliefs

- Stories we don’t believe in are lies, or fiction

- Stories we’re not sure about are hypotheses

An interesting question to ask here is ‘How do we start believing in stories? How does a story move from fiction to belief?’

Everything starts as a story created by someone. Some call it fiction, others call it lies, some others call it belief, and a small minority calls it a hypothesis.

For many of us, an oft-repeated story, spoken by people we love or admire, becomes a belief.

However, a small minority believes a different story. Their story says not to believe any story just because someone we love or admire said it. Evidence reigns supreme. This is the story of science and rationality.

Sometimes, stories materialise a little too easily. If a boss is scolding an employee, others can make up stories - hypotheses - about why this might be the case. When they finally hear from the employee, some, or maybe all stories become false, and the current story, as told by the employee, becomes the leading belief.1

The most common way of creating new stories though, is using templates we’ve heard before. More familiar stories give us more confidence in what’s going on.

For example, in the above example, consider three colleagues making up the story of what happened.

- Colleague 1: “He talked to aliens without reporting them”

- Colleague 2: “He banged the bosses’ wife”

- Colleague 3: “He made a mistake on the report”.

The first colleague’s story is wildly imaginative (and hard for us to take seriously), while the second and third are templates we’ve seen before. Given the boss isn’t going bat-shit crazy, it’s probably the second colleague’s story, and not the third’s.

Stories might have seemed invisible beforehand, but they’re our primary sense-making tool to understand the world.

Mental Models are Stories

Mental models are frameworks and heuristics that help explain the world. Sound familiar? They are stories we repeatedly tell ourselves.

This gives a second dimension to stories. If the X axis is degree of belief, the Y axis is degree of explaining-power.

Remember how we prefer stories we’ve heard before, fitting them into templates? The templates are our mental models. They are things we’ve seen happen.

All models are necessarily a simplification of real life - the map isn’t the territory, which means you lose some information when you create the model. The quality of the model depends on what kind of information you lose.

If a map of roads in your country removes all information about trees and their varieties, you’ll probably still find the map useful. However, if you’re a forester, this map is all but useless for you.

Hence, all models are wrong, yet some remain useful.

Stories are also a simplification of real life. Further, simple stories are easy to tell, easy to understand, and easy to spread. Complicated stories don’t go too far.

Bill Gates, on the story of his success, echoes the same sentiment:

“Steve [Jobs] and I will always get more credit than we deserve, because otherwise the story gets too complicated.”

Remember our couple in Heaven contesting the election results? They have a single story in their mind with no room for alternatives: The elections were rigged. They don’t have a story to help them test out new stories. They stick to their own story, until they find a new more powerful story to replace it.

Since mental models are stories, meta-mental models apply to stories too. This leads to interesting implications.

For example, a famous meta-mental model goes: “to the man with a hammer, everything looks like a nail.” Applied to stories, “to a man with a single story, everything fits into the same story.”

What can our couple in Heaven do about this?

The above example hints at another interesting implication: we can use stories to counteract other stories.

Cognitive biases are stories about human psychology. In the face of pressure, poor mental hygiene, or a great sounding story, we end up making catastrophic mistakes.

For example, availability bias is a story professing that what comes to mind first is usually not the complete picture.

This story is counteracting other stories.

It’s fighting simple stories that are top of mind. It’s a story telling you to beware of stories that have been designed to be so simple (and thus necessarily wrong) that they stay on top of your mind.

If the biases are cancer, learning the story to beware of them is chemotherapy.

Stories are a Vehicle for Change

A big question we haven’t yet touched upon is ‘Why do we tell stories?’

Stories move people. A story that moves us, compels us to change. It may not be enough to effect change, but it’s a necessary ingredient.

For example, people donate more to charity when they hear a story about one death, instead of a statistic about how many people died.

“A single death is a tragedy; a million deaths is a statistic.” - Identifiable Victim Effect

Telling new stories isn’t just for generating new hypotheses, but for eventually changing your mind, and forming new beliefs.

This third dimension of stories is how effective they are at driving action.

Because of this potency, advertising leads with stories instead of raw facts.

Not just advertisers - news channels do this too. A lot of news is telling new stories for you to believe. Depending on the news channel, there can be zero, or a lot of evidence supporting their stories. And, without a story to counteract these stories, you’ll either believe what they’re saying, without checking the evidence, or completely discard it, based on who is telling the story.

That’s exactly why kids believe everything they’re told when they’re small. They haven’t learned a story that says “Judge for yourself what is true - other people often tell lies to further their own agendas.”

There are three ways to counteract a new story that we’ve already seen:

- The Story of Science - the hunt for evidence

- The power of believing in only a single story - or the man with a hammer

- Learning about cognitive biases

The most effective statisticians are the ones who aren’t afraid to tell a story. - Seth Godin

The third meta-story has lots of heuristics, and lots of literature to explore.

Specific to advertisers, salesmen, and news channels telling you a story, one good way to counter their story is learning why you’re being told a story. If the storyteller has something to gain, and they’re a master storyteller, they’ll be able to move you to action quickly. Beware their motives for telling you a story.

All the warnings aside, if you can harness this power yourself - you can tell yourself compelling stories - then you can effect change in yourself. That’s something we’ll explore soon, too.

Stories Create Blindspots

Just like how all models are wrong, and some are useful; all stories are wrong, some are useful. It’s very easy to make useless stories sound useful.

For example, Seth Godin says:

When you talk about your last job, your last vacation, the things that happened when you were 12…

What do you lead with?

Do you lead with, “I broke my ankle that summer and rarely got out” or is it, “I stuck with my reading regimen and read all of Shakespeare.”

Because both are true.

The top story is the one that informs our narrative, and our narrative changes our future.

A story is a lens that is prone to framing: how you frame the story changes its focus. This creates blindspots.

Stories are never going to be the complete picture, so you must be aware of the parts your story focuses on - and the parts it leaves out - the blindspots.

The key here is to have multiple lenses: multiple stories that can compensate for each other’s blindspots.

As I wrote in Different Perspectives to Solve Problems - the inside and outside view are two stories making up for each other’s blindspots:

Taking both, the inside and outside view is better than just taking one. It’s like going to the eye doctor, where they show you unreadable letters on a lit-up screen. They add one lens on your eyes, and you begin to distinguish o and e. Then they add a second lens, and now you can even tell the difference between h and n! They add a third spherical lens, and the dots become sharper - you can now even see the dots over the i’s as circles, not blobs. Each lens is a perspective that sharpens your view.

For our couple in heaven, “they have a single story” could not possibly be a complete representation. It’s the part I chose to focus on. The problem, though, is more complex. It’s made up of tribalism, a lack of epistemic hygiene, social pressure, and echo chambers.

Learning from Master Storytellers

Since stories are a vehicle for change, we’d do well to learn how to tell ourselves stories.

At the same time, we’d do well to learn how others use stories on us to get what they want.

Further, we’d do well to learn how to tell stories to change other people’s mind!

All three follow the same principle: make the story compelling.

Our best bet to learn how to make stories compelling is to go to master storytellers: people in cinema, books, and advertising who tell stories that move and inspire us.

This section deserves its own post. I haven’t figured out everything here, but these are a few patterns I have noticed over the past year. There’s some book recommendations in the end that go deeper.

Dropped in the Middle

Some movies start from the middle: they drop you right into the action. Then, they explain how things got here, and finally catch up to the action, where things continue. This is usually necessary because the beginning just isn’t that interesting.

The non-linear sequence is a hook. Without it, you wouldn’t stay to hear their story.

Not just movies, but books, and even presentations, use this concept. It creates an open loop - it makes you curious about what they were doing there, and how they reached a situation like that.

Note that these don’t change the content much, just the delivery. And for most people, how we hear the story affects how much we believe it.

Ava is a recent movie that does this.

And if you want to dive further, here’s Kurt Vonnegut on the Shape of Stories.

Keep it Simple

Storytellers prefer simple stories because they’re more compelling. You don’t have to spell out all the details, you can just show them.

Further, repeating the story makes it familiar. And a Familiar Story is a Believable Story.

Respect the Frame

Imagine you’re watching a movie. The hero is a billionaire and wants to protect the world from powerful aliens. He built his own war suit, which allows him to stand up against the aliens.

The aliens, however, are cunning. They’ve become a part of society, and convinced people that they’re good. Nothing stops them from going on a killing spree, and that’s why our hero is rightly worried.

It’s not Tony Stark. Lex Luthor is the hero here, and Superman is the villain.

By first establishing who the hero and villain are, the story directs you to believe the hero’s story. That’s how Lex Luthor became the hero, and Superman the villain.

For a real world example, consider a news outlet presenting a case against a corporation.They first mention all the bad things the corp has done, like not paying employees (this establishes villainy) and then talk about how the corp ‘claims’ it didn’t know what it was doing. “If they didn’t treat their employees well, how can we believe this?”

Irrespective of the truth, it’s possible to frame a story however you want by using the right framing.

So, beware of charismatic people uniquely positioned to gain from the story they tell.

Show, Not Tell

If it seems like you’re the one telling yourself the story, your defences are reduced.

Master storytellers can nudge you into telling the story yourself, by showing very specific, thought out cues.

For example, this beautiful short story from Google.

Notice how the ad doesn’t have to say what’s happening. You fill in the blanks yourself.

Inside this desire to connect the unconnected is where good visual storytellers hide their ideas. - Adam Westbrook

Here’s another example, without any cues. What does this photo tell you?

It’s fascinating how people would look at the same chart and tell themselves completely different stories! Look at the replies.

Contrast

To make something look great, place it next to something clearly bad.

Stories that set up their objective in a backdrop of something bad instantly make their objective seem brighter. By showing a worse condition, your story shines through as a great option.

Contrast creates conflict, which triggers people’s attention.

Influence: Psychology of Persuasion covers this, and several related ideas, like establishing scarcity, in depth.

Leveraging Stories Told Before

Stories rush in and do your thinking for you; they substitute for seeing—the deadliest convenience of all. - modified quote from Eliezer Y, Seeing With Fresh Eyes2

Whacky stories are normalised by having parts connected to what people already know.

In The Best Things I Learned in 2019, I wrote:3

When I write, I want to expand the ball of knowledge in several directions. Maybe one spike will stick into something you already know, and that helps hang this spike along with the ball into your mental framework. You’ll then remember this longer.

The more ways I can explore the topic, the better. The more senses I can engage, the better. The more mediums I can use, the better.

The same is true for stories. The closer they are to something people already understand, the quicker they’ll get up to speed with the new story. Remember, a familiar story is a believable story.4

More Recommendations

Notice how I’ve used the same techniques above. It makes the message stick, and makes for clearer, compelling writing.

If this feels scary, you’re not alone. If you don’t want to ever fall for techniques like these, learning about them is a great first step. A second, harder but more useful step is to test out a new story: A Framework for Critical Thinking.

To explore these ideas further, try Invisible Ink and Alchemy.4

If you have more recommendations, I’d love to hear about them. Send me an email.

Four Powerful Stories

To end, here are four powerful stories that have shaped our world.

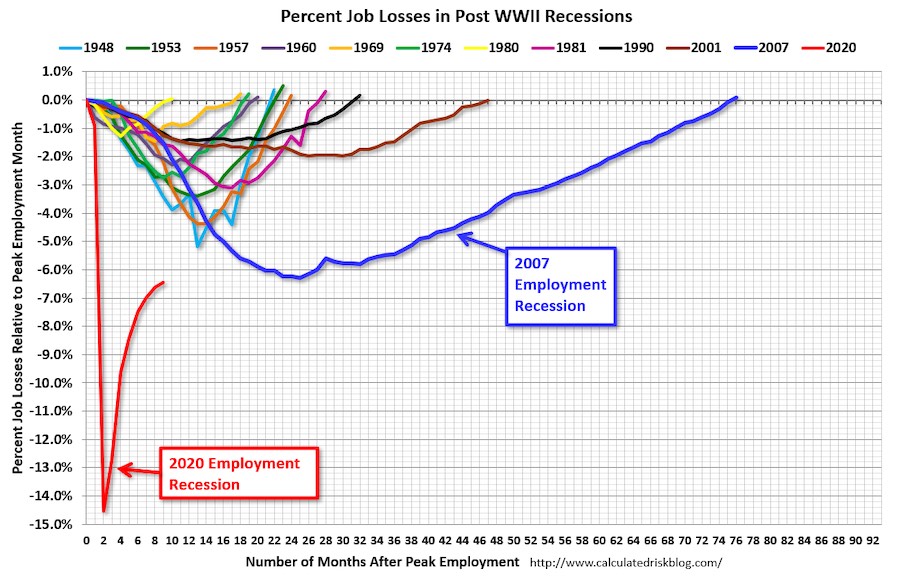

The Story of Recession & Economic Growth

If you snapshotted the world in 2007 and 2009, you couldn’t tell there was a recession in 2009.

You would have seen roughly the same number of people working, the same number of factories, and the same number of trucks moving between those factories.

Technology improved, computers became faster, mortality rates lowered, and social media exploded.

Why then, were the stock markets worth half of what they were worth two years ago? Why were there 10 million more unemployed people?

The intangible thing that changed was the stories we told ourselves about the economy. As Morgan Housel puts it, “In 2007, we told a story about the stability of housing prices, the prudence of bankers, and the ability of financial markets to accurately price risk. In 2009 we stopped believing that story.”

Read more about the nuances here.

The Story of Agricultural Revolution

Today, we believe the story that the Agricultural Revolution was a breakthrough, leading to population explosion, specialization, and finally, the Industrial Revolution. We’re glad our ancestors settled down, paving the way for the modern men & women.

Did our ancestors believe the same story? Were they proud of what they’d achieved? Or was it a living hell for them?

It’s hard to tell. Yuval Harari claims it was indeed a hell, and we’ve got the story all wrong. Our ancestors wanted to revert to a hunter gatherer lifestyle, but they were trapped. They had no idea about the story we now tell.

Rather than heralding a new era of easy living, the Agricultural Revolution left farmers with lives generally more difficult and less satisfying than those of foragers. Hunter-gatherers spent their time in more stimulating and varied ways, and were less in danger of starvation and disease. The Agricultural Revolution certainly enlarged the sum total of food at the disposal of humankind, but the extra food did not translate into a better diet or more leisure. Rather, it translated into population explosions and pampered elites. The average farmer worked harder than the average forager, and got a worse diet in return.

Read more in this summary of Sapiens.

The Story of Culture and desire

The culture shapes our desires. And the culture is a collection of stories passed from one generation to the next.

The elite of ancient Egypt spent their fortunes building pyramids and having their corpses mummified, but none of them thought of going shopping in Babylon or taking a skiing holiday in Phoenicia. People today spend a great deal of money on holidays abroad because they are true believers in the myths of romantic consumerism. Romanticism tells us that in order to make the most of our human potential we must have as many different experiences as we can.

A wealthy man in ancient Egypt would never have dreamed of solving a relationship crisis by taking his wife on holiday to Babylon. Instead, he might have built for her the sumptuous tomb she had always wanted.

And if you don’t believe in the story of romantic consumerism today, perhaps you believe in the story of minimalism, or the story of valuing experiences over possessions.

The Story of Growth vs Fixed Mindset

Do you believe your abilities are innate, or can they be learned? People who believe the first story have a very different life from people believing the second.

People with a fixed mindset - who probably haven’t heard of the growth mindset story - go about life avoiding failure at all costs. Intelligence is innate, which means they should never fail, or their intelligence isn’t as great as they thought.

People believing a growth mindset story lean into failure, and learn from it. They believe intelligence isn’t innate, and thus when experience tells them they were wrong, they learn from it.

The story you believe changes how much you can grow.

Conclusion

People tell stories and it’s an enormous part of what makes us human. We will do an awful lot for stories, and endure a lot for stories. And stories, in their turn, help us endure and make sense of our lives. - Neil Gaiman

We’ve seen how stories rule our world. Stories drive how we change our minds, influence other people, and learn how the world works.

Their sheer power makes them a double-edged sword. When we overly rely on a single story, nothing else seems to matter. The focus becomes too narrow, creating blindspots.

The only way out is to have other other stories ready to attack the main story. We saw five ways stories can counteract other stories

- The Story of Science - where evidence reigns supreme

- The man with a single story - where every other story is false

- The Story of Cognitive Biases

- The story of the Storyteller - and what they gain from telling us stories

- The Story of Blindspots

Thus ends the story of stories. They’re powerful. They rule our world.

Thanks to Susan, Julian, Matt, Kevin for reading drafts of this.

Have feedback? You can reply to this post on Twitter.

-

Complications - someone doesn’t believe, goes to the boss to figure out the “real” story. ↩

-

Original quote said Remembered Fictions, instead of Stories ↩

-

Also, this is me connecting this idea to something at least some of you have already seen. For more background, you could read this whole section ↩

You might also like

- Agentic Debt

- What I learned about burnout and anxiety at 30

- How to setup duration based profiling in Sentry

- How to simulate a broken database connection for testing in Django