Vocabulary as a Meta Mental Model

Pica is a condition in which people deficient in a nutrient experience cravings for things that don’t contain the nutrient. For example, people who are iron deficient find themselves chewing on ice cubes.

The body’s ability to identify the nutrient isn’t great, so it applies various heuristics: if it’s hard or if it looks rusty, it might have iron. So, the same people sometimes eat dirt, too.

This is an excellent metaphor for many things we do in life. We find ourselves watching sitcoms because we want to feel like we’re surrounded by friends, or relentlessly playing mobile games because we want to feel a sense of progress and accomplishment, or buying new clothes because we want to change something deep about who we’ve become.1

We’re eating ice.

Sometimes, knowing the name is good enough.

Most cognitive biases work that way. Once you find out what availability bias is, you can figure out where you’ve fallen for it. Noticing availability bias without knowing it is much harder.

It’s the same for emotions, ideas, design patterns, and specific situations in life. Having a name helps you notice.

Sometimes, there’s a solution built into the name.

For example, I love watching isekai anime. It’s a hero’s journey in a virtual world. An unimpressive person from Earth, overpowered in the parallel universe. Tsuyoku Naritai! I want to become great, so I’m attracted to anime like these. I’m unimpressive, so I love watching how my anime counterparts navigate the world.

This is me “eating ice”.

Solving this can be as easy as introspecting and figuring out what I need. When pica patients start taking iron supplements, the craving to eat ice or dirt disappears.

But sometimes the problem is illegible. There’s no obvious solution in sight. In this case, eat dirt instead of ice. Dirt has some amount of iron, while ice definitely doesn’t.2 It’s a step in the right direction.

A supplement can’t help me achieve greatness or find self-worth. The equivalent of “eating dirt” here means trying new things. Use exploration and empiricism instead of reasoning to take a step in the right direction.

Knowing the name of this idea gives you a scaffolding to hang your mind on. The name triggers the example in your mind.

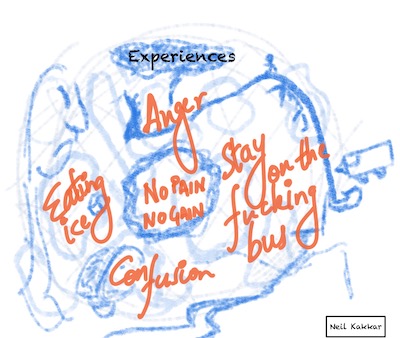

“Eat dirt, not ice” and stay on the fucking bus are a lot like “No pain, no gain”, or “All good things come to an end”.

They might seem very different, since the latter are already part of your vocabulary, while the former ain’t. Having models like these gives you a richer sense of the world when making decisions.

They’re all categories about things that happen, and have some hints on how to act in these cases.

Eating dirt, not ice is about setting the right direction for your efforts.

Stay on the fucking bus is about being persistent in your approach to creativity.

No pain, no gain is about doing the work first, and thinking about the outcome later.

All good things come to an end is about being wary and enjoying what is.

The difference is that the prescription about what to do doesn’t help you recognise where things are going wrong in the first place.

“Make sure you’re moving in the right direction” doesn’t help me recognise patterns where I’m eating ice. It’s too abstract to be helpful. Knowing the story about ice and dirt shows me how I fall off the right direction. It helps me pattern match while I’m on the path to making dumb decisions, not after the fact.

Experience does exactly the same. Once you know what Availability Bias is, you notice yourself falling for it. Once this happens a few times, these situations become your stories to pattern match. Of course, if you don’t have a system to log them, you’ll go through a lot more mistakes before you find them.

The “Eat dirt, not ice” story is a shortcut to experience.3

Chunking

I’ve written before about how vocabulary can aid learning, but I didn’t see the forest for the trees.

The names are the vocabulary. They’re also categories of stories and experiences.

If you have more categories, you can categorise things better. I think building these categories is worthwhile.

Having a common name for a situation is a chunk you can unpack when needed. That’s what all adages, aphorisms, and proverbs are.

In simple cases, knowing the name is all you need. I’d put almost all cognitive biases and half of psychology in this category.

In complex cases, just knowing the name wouldn’t suffice. But this still serves an important purpose. It brings the situation into the “things you know that you don’t know” bucket. Without the name, they stay in the unknown unknown.4

I suspect, as civilization progresses, we’ll have a lot more proverbs as a part of regular speech. Our combined language will chunk more complex topics together.

But, for personal development, waiting for the culture to catch up is awfully slow. Instead, you can be earnest about it. You can hunt for these ideas.

We are prepared to see, and we see easily, things for which our language and culture hand us ready-made labels. When those labels are lacking, even though the phenomena may be all around us, we may quite easily fail to see them at all. - Douglas Hofstader

Where to expand

Go out of your way to explore cultures and languages to obtain new vocabulary.

This doesn’t necessarily mean learning a new language.

I learnt French a few years ago, and I found this very amusing:

“I know” translates to “Je sais” and “Je connais”. You say “sais” for facts, and “connais” for people. I suspect the French who learn English find it surprising that we could combine these two categories together! Just like how I find it surprising that they could split these categories into two.

However, this is a very small thing. The new ideas I developed while learning the language weren’t many.

Diving into a culture dense in information has higher chances of containing vocabulary you don’t know.

Don’t learn a new language. You’ve covered what regular people talk about.5 Instead, dive deep into fields you know nothing about. Economics, Psychology, Philosophy, Physics, or applied rationality.

CFAR has excellent material, like this handbook, from which I got the idea about eating dirt, not ice.

This is what mental models are: ideas from diverse fields that can aid your life. In this sense, improving vocabulary is a meta mental model. It’s a way of finding and organising new mental models.

Why I think names work

Why do bird watchers name every bird species they find?

In a family of thrush, throat color may be all it takes to identify a bird. Then, naming the thrush can be as simple as “Black-breasted” or “Black-throated” thrush.

When similar thrush don’t exist on the same continent, naming them “African” or “Chinese” is enough to disambiguate.

Categorisation like this can be worthwhile to figure out the axes on which things differ.

Other times, naming helps trigger a concept. It’s a chunk. Like “eat dirt, not ice”.

The collection of names is a dictionary. It helps you map different experiences to the same name. Not knowing which name to pin an experience with is a sign of confusion - you’re missing a category. If lots of different names fit, it’s a sign of nuance and complexity. Perhaps, it’s a lollapaloza effect.

The bigger the chunk, the more our mind can hold. Names are excellent for creating larger chunks, since when done right, they pack lots of information into a single sentence.

Fun Fact:

Chunking is one technique how memory experts remember long strings of numbers. It’s also how you remember a phone number with digits in pairs of two or threes instead of in isolation.

For example, 9 - 8 - 1 - 0 - 0 - 2 - 7 - 5 vs 98, 100, 275.

Beware though. Don’t confuse knowing the name of something with knowing something. Or try to guess the teacher’s password. Or assume everyone will have the same contextual unwrapping as you.

Categorical errors

None of this means the categories you have are enough to solve your problems.

Applying one category, or your favourite categories everywhere doesn’t help.

Maslow’s Hammer: To a man with a hammer, everything looks like a nail.

As you get more and more categories, you’ll realise that they contradict each other.

For example6,

“Pen is mightier than the sword” vs “Actions speak louder than words”

“If at first you don’t succeed, try, try again.” vs “Don’t beat your head against a stone wall.”

“Absence makes the heart grow fonder.” vs “Out of sight, out of mind.”

“You’re never too old to learn.” vs “You can’t teach an old dog new tricks.”

“No one is perfect” vs “Practice makes perfect”

What the name misses is the context. If the name doesn’t trigger experiences or stories, you have no context to go on. You need to unpack the ideas from the name, figure out the context they work best in, and then apply it. This is hard.

Mastering these categories and where they apply will take time and experience. However, knowing the contradictions in each category helps master the category better. We’re using inversion to define the limits of the category.

Knowing where an idea doesn’t fit can be just as valuable as knowing where it fits.

Vocabulary as a meta mental model

The better your vocabulary, the more things you can name, the richer your base of raw materials to hang new ideas and experiences on.

The better your vocabulary, the more aware you become about possible categorisation errors.

The better your vocabulary, the more stories you can chunk, the more experiences you can pattern match.7

Improve your vocabulary.

Thanks to Dev Kakkar for reading drafts of this.

-

This first section is heavily inspired from CFARs handbook. ↩

-

All for the metaphor. I’m not a doctor, this isn’t medical advice. The recommendation comes from CFAR, too. ↩

-

It’s a lossy compression. You do lose out on details. If the story had every detail, it would be just as long as the experience. But not everything is important. So, a good story is one that captures the most important information. ↩

-

Unknown unknown is the set of things you don’t know that you don’t know. ↩

-

For the purpose of improving your vocabulary and collecting new ideas. ↩

-

I’ve used proverbs that are a part of general vocabulary already. When working with bigger chunks, the stories become more nuanced, and the contradictions less visible, but they’re all still there. ↩

-

This makes it sound like any vocabulary makes a good story. As we’ve discovered before, that isn’t the case. There’s a bit more nuance to it. ↩

You might also like

- Agentic Debt

- What I learned about burnout and anxiety at 30

- How to setup duration based profiling in Sentry

- How to simulate a broken database connection for testing in Django