The Dunning Kruger Effect

A few years ago, my younger cousin beat me at Chess in 3 moves.

I’m pretty sure Fabiano Caruana could beat me in 3 moves too. Using this data point, how do I figure out who is better? To me, my cousin is on par with Fabiano.

However, Fabiano Caruana is currently ranked #2 in the world, and my cousin isn’t on the leaderboard, yet.

Oh, if my cousin is on the same level as Caruana, and both are somewhat better than me, I definitely must be above average!1

There’s a lot more to the Dunning-Kruger effect that pop culture misses out. I got my hands on the original research paper and dived in. These are my notes, plus hints on how to deal with it.

What is the Dunning Kruger effect

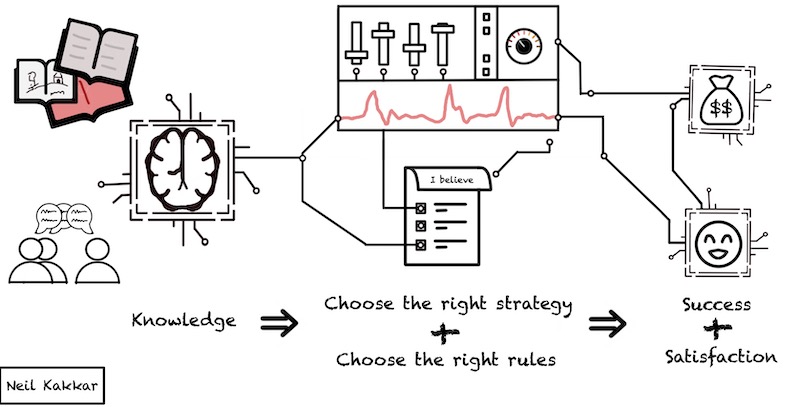

In many domains in life, success and satisfaction depend on knowledge, wisdom, or savvy in knowing which rules to follow and which strategies to pursue.

For example, hacking systems depends on figuring out the real rules. Some ideas are literally false, metaphorically true which give you an edge over others.

People also differ widely in the knowledge and strategies they apply in these domains.

When people adopt incorrect strategies, not only do they reach wrong conclusions and make unfortunate choices, but their incompetence robs them of the ability to realize it. For example, average people tend to believe they are above average (like me in Chess!).

That’s the short version. In the long version, the paper makes 4 broad predictions.

Prediction 1: Incompetent individuals, compared with their more competent peers, will dramatically overestimate their ability and performance relative to objective criteria.

Prediction 2: Incompetent individuals will suffer from deficient metacognitive skills, in that they will be less able than their more competent peers to recognize competence when they see it — be it their own or anyone else’s.

Prediction 3: Incompetent individuals will be less able than their more competent peers to gain insight into their true level of performance by means of social comparison information. In particular, because of their difficulty recognizing competence in others, incompetent individuals will be unable to use information about the choices and performances of others to form more accurate impressions of their own ability.

Prediction 4: The incompetent can gain insight about their shortcomings, but this comes (paradoxically) by making them more competent, thus providing them the metacognitive skills necessary to be able to realize that they have performed poorly.

Together, they form the Dunning Kruger effect.

When people adopt incorrect strategies, not only do they reach wrong conclusions and make unfortunate choices, but their incompetence robs them of the ability to realize it.

Dunning and Kruger try to establish cause using Prediction 2 and 3. They set up four experiments to test this (and confirm Prediction 1 each time). They tested on a sense of humour, logic, and grammar. In each case, participants assessed their ability after the test. I won’t go into the tests (it’s all in the paper), but what it means for us.

Let’s take each one in turn.

Incompetent people think they are better than they are

Popular culture talks extensively about this. People who are incompetent think they are the best. Herein lies the first misconception. People who are incompetent think they are better than they actually are, not that they are better than the best!

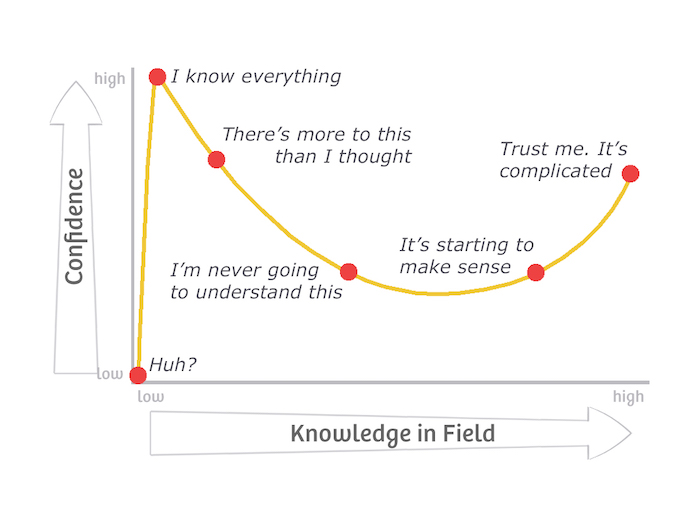

The paper doesn’t talk about confidence, either. This makes this popular graph more of an artistic interpretation than the actual effect:

Not really? Source

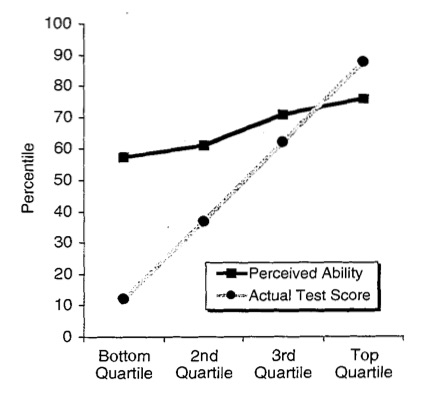

While the paper says this:

from the research paper

There’s a crucial difference. Incompetent people may estimate they are better than average, but their confidence in this estimate might be lower than “high”. The perceived ability != confidence. 2

People with almost zero knowledge don’t think they “know everything.” They think they know more than they do. It’s still less than what competent people know.

Another popular misconception is that the DK effect claims “beginners are way overconfident”. However, all it says is “poor performers are way overconfident.”3

Going back to the actual graph, there are two possible ways for the perceived ability graph to form. Participants may have overestimated their own ability or may have underestimated the skills of their peers.

The paper concluded that

-

The top-performers underestimated their own ability because they overestimated the performances of their peers, falling prey to the false-consensus effect.

-

The bottom-performers overestimated their own ability.

The criticism section explores alternative explanations.

Incompetent people don’t recognize competence when they see it

Not only do incompetent people think they are good, but they don’t recognize the real great people.

Thus, they can’t learn from them. Thus, they don’t improve. Thus, they are destined to stay as they are.

Richard Nisbett said of the late, great giant of psychology, Amos Tversky. “The quicker you realize that Amos is smarter than you, the smarter you yourself must be.”

Back to the Chess example I began with, it’s hard for me to judge who is better: my cousin or Fabiano.4 Of course, in a 2 player game like Chess, I might be able to figure out who is better if I get them to play together. But what if it’s an infinite player game, like being good at logic?5

Metacognition is this ability to think about and judge your thinking. It’s a skill separate from how well you learn (cognition).

Incompetent people don’t learn from their peers

One of the ways people gain insight into their own competence is by watching the behavior of others.

Because of their difficulty recognizing competence in others, incompetent individuals will be unable to use information about the choices and performances of others to form more accurate impressions of their own ability.

Despite seeing the superior test performances of their classmates, bottom-quartile participants would continue to believe that they had performed competently.

On the other hand, top performers learn from observing responses of others.

The problem with failure is that it’s difficult to figure out the root cause. For success to occur, many things must go right: The person must be skilled, apply effort, and perhaps be a bit lucky. For failure to occur, the lack of any one of these components is sufficient. Because of this, even if people receive feedback that points to a lack of skill, they may attribute it to some other factor.6

Incompetent people can learn they are incompetent..by becoming competent

Or as I like to call this, “When you can figure out you’re shit, you’re not shit anymore.”

This is the most exciting result to me. Thinking of metacognition again, I’d divide it into two: General and domain specific.7

General meta-cognition is what enables me to seek out what I don’t know.

Specific meta-cognition is what enables me to understand how much I don’t know about a specific subject.

If I can hone my general meta-cognition, I can ensure I don’t fall for the Dunning-Kruger effect in whatever domain.

How to stop yourself from falling for the Dunning Kruger effect

“The first rule of the Dunning-Kruger club is you don’t know you’re a member of the Dunning-Kruger club. People miss that.” - Dunning

What’s interesting about the studies is that they offer clues to when you’re falling prey to the DK effect.8

Every time I think – “I am above average, of course” – an alarm bell needs to go off in my mind.

How do I know I’m above average?

As the studies suggest, get to know your peers and what they are doing. If you can distinguish who is bullshitting and who isn’t, maybe you do know what you’re doing.

If not, uh oh. That should be enough of a warning to dive deeper into whatever you’re learning - switching to specific meta-cognition.

In many cases, incompetence does not leave people disoriented, perplexed, or cautious. Instead, the incompetent are often blessed with an inappropriate confidence, buoyed by something that feels to them like knowledge. - David Dunning

Another antidote I’ve come across is the Stoic art of premeditatio malorum, or pre-meditation of evils. Assuming you’ve failed, or found out you are objectively bad at something - how are you going to explain it? Would you call it just a bad day, or something deeper?

Depending on how many times you face this failure in real life (a proxy for competence), the answer ought to transition from “a bad day” to “I am shit”.9

Again, once you do know you’re shit, you aren’t unaware anymore, and can work towards fixing it.

“Real knowledge is to know the extent of one’s ignorance.” - Confucius

Domain Dependance of the Dunning Kruger effect

The effect doesn’t show up everywhere. There are a few caveats. One big caveat is the domain under consideration.

In some domains, knowledge implies competence. For example, someone who understands inferential logic will be a competent logician.

In other domains, competence depends on other factors too, like physical skill. For example, soccer coaches probably know what they are doing, but I can’t imagine Sir Alex Ferguson playing a 90 minute game now. He’s not competent at playing soccer. Despite this, he has the knowledge to realise when one of his players is making a mistake in the game.

In domains where knowledge implies competence, lack of skill implies both the inability to perform competently as well as the inability to recognize competence, and thus are also the domains in which the incompetent are likely to be unaware of their lack of skill. Or, the domains in which the Dunning Kruger effect runs rabid.

In other domains, not so much. If you can’t dunk, you probably aren’t under the illusion you can make it to NBA. If you can’t serve, you probably don’t think you’re Wimbledon material. But again, that doesn’t stop some average blokes from thinking they can win a point off Serena.

Finally, in order for the incompetent to overestimate themselves, they must satisfy a minimal threshold of knowledge, theory, or experience that suggests to themselves that they can generate correct answers.

Remember that this is a statistical effect. It doesn’t mean you will fall for it, but a majority do. And the same majority thinks the effect is for dumb people out there in the world. But, we know better now. It affects everyone, is domain specific, and isn’t about dumb people.

Criticism

Another paper claimed reversal of the effect in extreme situations, to which David Dunning responded as far from reality (the extreme situation, not the result).

There are quite a few other criticisms. The most standard being that the effect is simply a regression to the mean coupled with self-enhancement.

For incompetent people, not only do their perceptions of their own performance regress toward the mean, but those perceptions are also further inflated by the self-enhancement bias. In contrast, for high performers, these two effects largely balance each other out: regression to the mean causes high performers to underestimate their performance, but to some extent that underestimation is offset by the self-enhancement bias.

However, whatever the reason, the effect still stands. The criticisms are for the meta-cognitive ability. Given how the meta-cognitive explanation suggests a way to overcome the DK effect, I’m willing to stick with it for now.

-

Wat? 🤔 ↩

-

There’s definitely an element of over-confidence involved, but it’s not what the paper measured. ↩

-

What’s really cool about this misconception is that it suggests there’s a way for beginners to shoot past the poor performers. I explore this a bit further below. ↩

-

I used Fabiano as an example here assuming people don’t know about him. The idea is to compare people using just your datapoint of playing against them. ↩

-

The kind of game where you don’t need to pit players against each other to figure out who is better. They are all in a race together. It’s a leap from ordinal to cardinal ordering ↩

-

Also known as the Anna Karenina principle ↩

-

My artistic rendition, not a part of the paper. ↩

-

This is us honing our general metacognition right now ↩

-

This is us honing our general metacognition again ↩

You might also like

- The Best Things I Learned In 2019

- If Sapiens were a blog post

- How To Understand Systems

- Algorithms to Live By