What I learned about burnout and anxiety at 30

If I had to choose one moment that signifies the deepest shift in the last few years, it would be mid-2024 when I had my first and only panic attack. It was my body and mind finally protesting and giving up, being like, “Neil, fuck this shit. You are not seeing the signs, so I have to take some drastic measures.”

It caught me completely by surprise. I did not know what was happening to me. It felt like a serious illness, and in a way I guess it was, just more mental than physiological.

Think of life like a four-legged stool. It’s super sturdy with four legs. It’s still pretty damn sturdy with three legs. Go down to two, and it’s hard to stabilise on most surfaces. At one, you’re definitely falling over, the only question is how slowly.1 At zero, you don’t have a stool left, you’re a pancake.

I think these four legs are emotional connections, physical activity, hobbies, and work.2

And I, became a pancake.

The slow slide

I was deep into work. I became a manager, became responsible for high-profile client-facing features, and cared a lot about what we were building at PostHog. It was a wonderful time of growth, punching above my weight, learning a lot, but also doing too much of it. I was switched on all the time, and escaped into fantasy novels afterwards. It.. wasn’t healthy. And I didn’t realize it until it all came crashing down.

Thus began my long and slow road of dealing with anxiety. It was there long before the panic attack, but I did not understand what it was. It showed up as this compulsion to go back home, read some manga, and escape into fantasy novels. That felt.. safe.

I was also getting lonely. I had friends, but I rarely went out to meet them. Almost every time I did go to a social event, I adored it. Every time I had to decide to go to an event, I dreaded it. I thought I had too much work, and I wanted to relax after work by myself. I couldn’t be bothered to go out.

As the 2019 me thought about it, life is a complex adaptive system. Every part of life is an input to some other part of life. I theoretically understood it, but the visceral feeling of experiencing it is different.

The signs I missed

Observation is my superpower, but it’s a lot more retrospective than I would like. I’m not good at catching things in the moment, yet. It’s hard and it takes a lot of time.

I spent so long observing and tracking things that I stopped listening to my body and instead only “heard” hard metrics I could see. It’s the classic Goodhart Law, I did not expect it to apply to my body and mind.3

One of these signs was reflux. I started having reflux problems about a year and a half before the anxiety attack. It was frustrating, but not debilitating. I ran experiments to figure out what foods trigger it, broken down by time of day, and over time got a much deeper understanding of my body. However, this was treating the symptoms, not the cause. Reflux became much rarer after I quit.4 I’ve talked so much about systems but failed to see this connection in my own system.

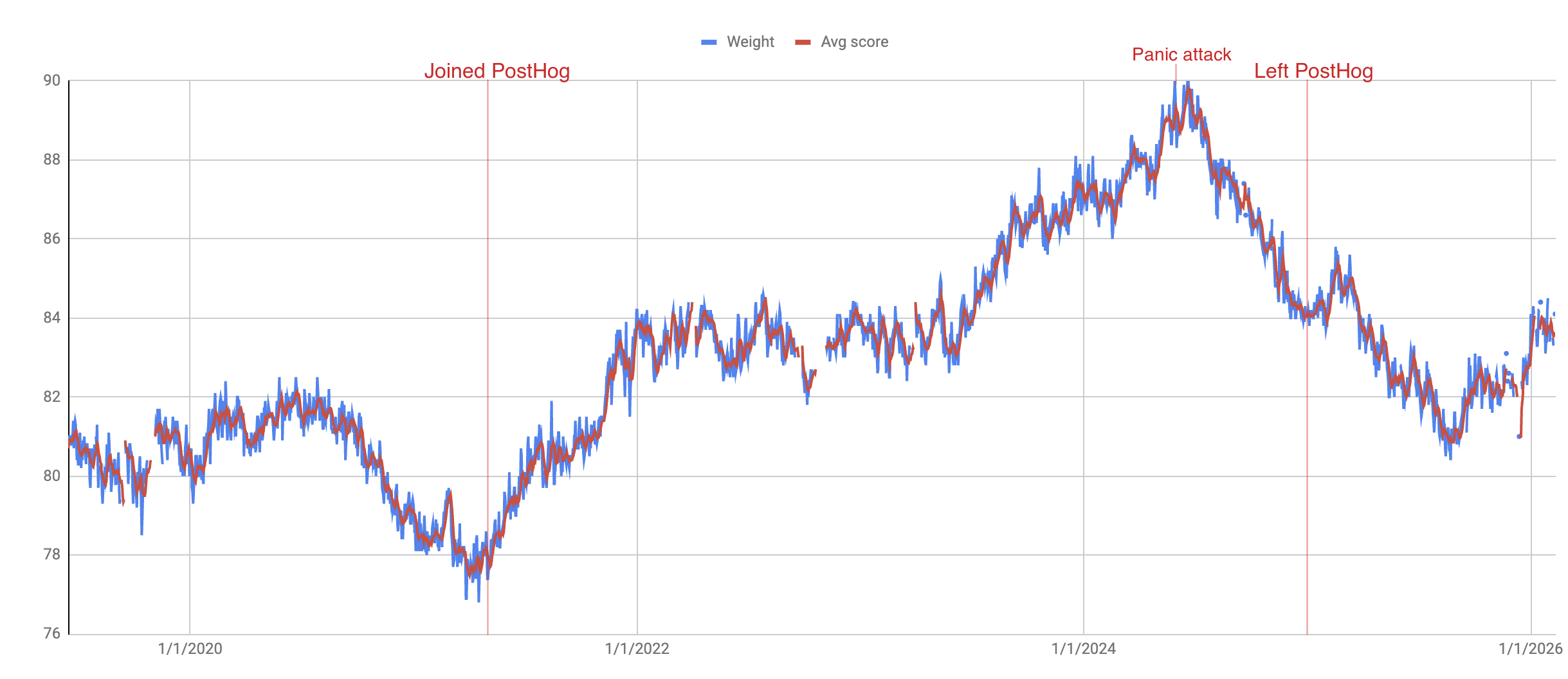

Another sign was the weight gain. This graph was going up and to the right - and this is one of those graphs you definitely do not want on a hockey stick trajectory.

The data collection was manual here. I was inputting these numbers every day. I was seeing the graph every week. The alarm bells still failed to trigger, or when they did trigger, they were silenced. “It’s fine, I’ll start working out again when I have more time”. “Kicking myself over it doesn’t help me feel better”. “I already have enough on my plate”.

Present me would treat this a lot more seriously than past me. The inner monologue above suggests things have gone very much out of balance. It’s a stool missing one of its legs.

A third wedge that further complicated the above was this iron deficiency I didn’t know about. Borderline iron levels don’t get flagged on blood tests, but can cause fatigue and post-workout dizziness. Thanks to the NHS doc who noticed it after several others glossed over it.5

This also made my anxiety much worse - and for a while I was wrongly attributing the tiredness to anxiety, and turtled in quite a bit.

But still, I’m glad it came crashing down in 2024 rather than in 2028. The faster I understand, the faster I can course correct, and that’s exactly what 2025 has been about.

Rebuilding

I quit my job in January, after 6 months of trying to figure it out while keeping the job. I couldn’t bring myself to work anymore, and it was better to stop than drag it out. It wouldn’t be fair to my colleagues, and I’d feel much worse about coasting and making excuses too.

What followed was a period of lots of joy, new routines, new hobbies, and pushing my limited self to feel whole again. I discovered a love for board games, made lots of new friends, played a lot of tennis and pickleball, which made me realise how much I was missing out on.

It was slow though. Anytime I got impatient and pushed too hard, the anxiety would creep back in. This was.. weird. I was so used to pushing ahead that slowing down felt awkward. I was impatient to recover. Over repeated instances, I learned to calm down.

What feels like “pushing” can be true for even the smallest of things. For example, in the early days, I “pushed” myself when I went out to watch a movie with a few friends. It felt miserable. I felt trapped in my seat, watching the gore in Deadpool. This made me feel worse - “Why am I feeling like this? These are all things I used to enjoy?”. It spirals so quickly when I’m not noticing. I dipped to the bathroom to catch my breath, and went on a walk after to calm down. I decided that was enough adventure for the week, and turtled back at home.

I wouldn’t have gotten out of my new shell at all, had I not pushed; but I also couldn’t push too hard. It was important to take things slow, but to also test the edges of my capabilities. It’s like running evals for an LLM - we do it because we don’t have a good intrinsic understanding of AI model capabilities. I didn’t have a good intrinsic understanding of my limited self’s capabilities, so I ran my own evals. The difference is I’m not static. The act of testing my capabilities extends them, and sometimes shrinks them.6

However, my body doesn’t always align with what my mind wants. There’s always some apprehension in the body - call it anxiety, call it nervousness, call it jitters, call it excitement.7

Over time, this apprehension doesn’t go away. I have just gotten better at dealing with it. Enough examples of going out and having fun reinforces this idea that there’s nothing scary.

I still close off sometimes though, and that’s okay. Sometimes I just want to be comfy, and so I be comfy.

What I’ve learned

Looking back, a lot has changed in the last 5 years. The overarching theme is that theory sounds nice, but reality is messy. 2019-me was directionally correct. I would be in a much worse spot today if I didn’t think through life the way I did and lay down my principles.

Reality has a surprising amount of detail, and systems need reinforcement. Knowing what was happening and why it was happening wasn’t always enough to make a change. I needed the lesson drilled into me.

I felt the same about my second year of work review coming across as overconfident.8 And yeah, it was. But I still stand by it. If I don’t see myself as who I want to be, it’s much harder to reach where I want to be.

Environment > willpower

Structural design wins. I’ve yet to see success with willpower based resolutions. Maybe I’m weak-willed, but I’ve learned to stick to what works best for me.

My internal monologue still goes at it wrongly - “I need to go to bed early”, “Don’t eat greasy food late, it will give you sleep problems”, but what helps the most is designing my life such that this happens by default.

An 8 AM alarm every day means I’m usually too tired to stay up late, and works wonders for my sleep. It’s not the whole picture though. Everything is connected, and if I’m too stressed at work, stress-eating late at night, and then revenge bedtime procrastinating9 - then I invariably end up sleeping poorly. Fixing this doesn’t mean fixing sleep, it means fixing whatever else is broken, and sleep will fall back into place.

Every lasting behaviour change I’ve made has been environmental, not motivational. It was magical how many of these problems went away once I quit.

No junk food at home does wonders for healthier eating. SAD lamps make winters happier. Cold, dark room leads to much better sleep. Good sleep instantly elevates the day. Moving houses made me realise how important sunlight is to me. A living room full of sunshine sparks so much joy. As do regular weekly tennis sessions.

I can change things to be the way I want them. I can ask more of the world than the default.

Stress reveals itself through control

When I can’t wind down after work, when I am always on - that’s a sign of stress. That’s a sign I can’t shut off. That’s a sign I need to change things.

When I’m stressed, I grip tighter. I want to fix things so they stop being a problem. I feel the stress will go away when the problem has gone away. I keep thinking about the problems no matter what I’m doing, which causes more stress. This is counterproductive.

I’ve learned to trust myself, to let go. This is where high observation becomes somewhat of a burden. Tracking metrics when they’re all going poorly causes a bit more extra stress. Which in turn causes me to grip a bit tighter.

Sometimes, I need to walk away from the environment that incubates this stress. That’s why I quit my job.

The same patterns repeat

This is surprising. My first work review was very cerebral - things I’d learned, how to test code, frameworks to think about code design etc. etc. My second work review was a lot more.. emotional. Looking at the soft skills, how it feels to take on a big new challenge, the fear of failure, etc. etc. The loop was much faster - these posts came out over two years.

Now, this same pattern is repeating over six years of life reviews. The first post was all about frameworks on how I want to design my life, the next few years were about implementing it and seeing them fail. And this post is the culmination of those patterns. Some did well, but what became more important is how I felt, how I overcame challenges, not just intellectually, but by teaching myself to listen to my body, and being comfortable with anxiety. When I embraced it, felt it for what it was, and repeatedly felt that experience over months, anxiety the “bad thing” finally went away.

These same patterns show up at the micro level too. I have to rediscover the same things again and again for it to stick. I’m very much like an LLM in this sense, I need to experience a lot more examples than one would expect before it sinks in.10 Especially when it comes to complicated, non-intuitive situations, or where intuition leads me astray.

I sacrifice stability for growth

…and I still like this a lot. Sure, it leads to problems, and instability over time, but I’d do it all over again. Would I make better decisions given I know what I know now? 100%. Would I refrain from jumping into the next big thing worrying over whether I’ll fall in the same loop again? Nope. I might still flounder in a different way, but as long as I learn from it, as long as I grow, that sets me up for a more successful third loop.

It’s a trade off I’m very willing to make. Compared to 2019-me, I’m more resilient, a little wiser, and most importantly, more content.

Four legs on the ground again, it’s time for the next adventure!

-

In micro-gravity, it might take very long. ↩

-

And maybe it’s not a stool, but an N-dimensional object, which requires N+1 legs to be stable, and I don’t realise these other legs exist because they’ve never been absent in my life for long. Or maybe just like in a Principal Component Analysis, the first four dimensions account for majority of the stability and the others don’t affect things that much. Or maybe I should stop stretching this analogy so much. ↩

-

“When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure”. This happens in organisations all the time. Inspired by Peter Drucker’s timeless wisdom, “What gets measured gets managed”, the quest to measure metrics begins, as it did for me. However, what’s easy to measure isn’t always what determines overall health. For example, weight increase is good if I’m gaining muscle mass, but bad when I’m gaining fat. Weight is much easier to measure though than muscle mass, so 🤷♂️. ↩

-

Why not gone completely once the stress is gone? Again, the body is a complex adaptive system, and once the gut health is fucked, it seems like it takes a lot longer for it to go back to normal. ↩

-

And a lesson for me to run Claude / ChatGPT over my blood reports. I don’t know if the 2023 models would’ve caught it, but the early 2025 one definitely did, and managed to connect with the slightly off values in other parameters. And these models are only getting better 🤯. ↩

-

When I push too hard. ↩

-

I’m glossing over this right now, but the way I frame it makes a huuuge difference! My relationship with anxiety is a lot less negative now than it was initially, and I imagine for a lot of people anxiety is a “bad” word. So when you frame the jitters as anxiety, it seems like a bad thing is happening to you, which leads to avoiding it. I’ll maybe talk more about this in a separate post - let me know if you’d like to hear more about it. ↩

-

and it got trashed on Hacker News for the same, as expected 😂 ↩

-

“Learned a very relatable term today: ‘報復性熬夜’ (revenge bedtime procrastination), a phenomenon in which people who don’t have much control over their daytime life refuse to sleep early in order to regain some sense of freedom during late night hours.” - tweet deleted now, and I don’t want to link to news slop. ↩

-

And this is the third time I’ve referenced this idea of repetition to make things sink in, in a different way. Co-incidence? I think not. ↩

You might also like

- Agentic Debt

- How to setup duration based profiling in Sentry

- How to simulate a broken database connection for testing in Django

- The "People fuck up because they're not like me" Fallacy