Games People Play - The Blogpost

Have you ever had your boss pass their mistakes on to you?

Well, Bob the Boss does. At a critical meeting, Bob asks his team for suggestions on how to fix things. Alice shares an interesting idea, and Bob takes it to upper management. However, it ends up making things worse. Tough luck. Bob then redirects all the blowback to Alice. “Look what you made me do, Alice! Fix it, it’s on you now”.

Bob is playing a game of “Look What You Made Me Do”. He’s setting things up so the blame never lands on him. He’s vindicating himself. If you can relate to this game, you’re not alone. There’s hundreds of games people play, and psychologists have spent years studying these games.

However, all is not lost. If you figure out the game and play the right moves, you can stop these games.

- You can stop your manager from shirking off responsibility.

- You can stop your spouse from playing status games.

- You can stop your friend from messing up their life and seeking sympathy again and again.

- You can stop strangers from playing games with you, too.

But that’s only if you know the game they’re playing.

Games People Play1 is a repository of such games and how to stop them. Eric Berne spent 40 years studying these games and published an academic book. I spent a month plowing through the literature, took the best parts and stitched together a narrative of the most important games, with examples relevant to today’s age.

We’ll start with some background theory — just enough to make sense of things. Then, we’ll explore interesting games people play, like the one above, and figure out ways to stop them. If you don’t want the background, you can skip directly to the games.

Background

To understand games, we need to understand how people behave, and how this behaviour changes in front of others.

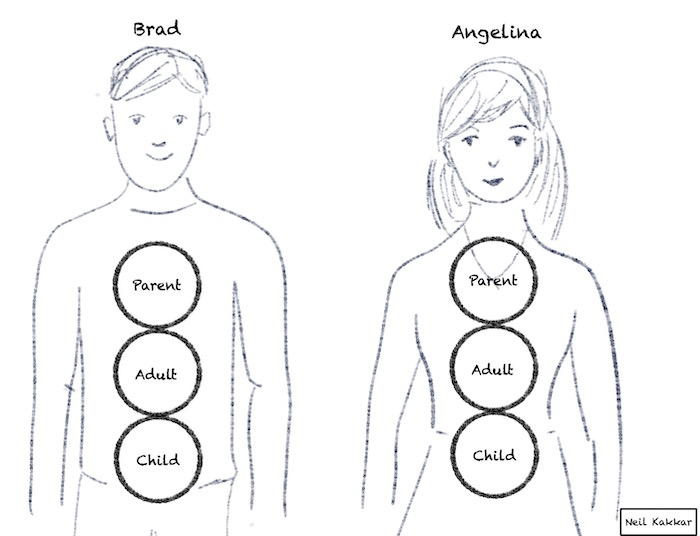

People have a set of behaviour patterns that correspond to one state of mind, and others that correspond to another state of mind, which are often inconsistent with the first. These different states of mind are ego states.

Eric Berne, the author of Games People Play, says there are 3 big ones: The Parent, The Adult, and The Child. These ego states are different modes of operation in every person.

The Adult is the rational logical self. The Parent is the caring, taking care of someone self. The Child is the playful, creative, easily offended self.

Note that these states have nothing to do with being a child or a parent yourself. A child acts from the Parent state when she tells their parents “I didn’t like it when you did this. Please don’t do it”.2

Sometimes, you can notice people transition from one state to another in conversation. For example, when Alice and Bob are discussing a problem and Bob claims that Alice is wrong, then Alice might get triggered out of the Adult state to a Child state where they start crying, or create an uproar, or call their mother to tell how Bob is wrong and mean. The transitions show up in physical gestures and posture too.

To understand people, you need to understand their ego states. To understand ego states, you need to interact. This is the core idea of Transactional Analysis. Games People Play are built on top of Transactional Analysis.

Transactional Analysis

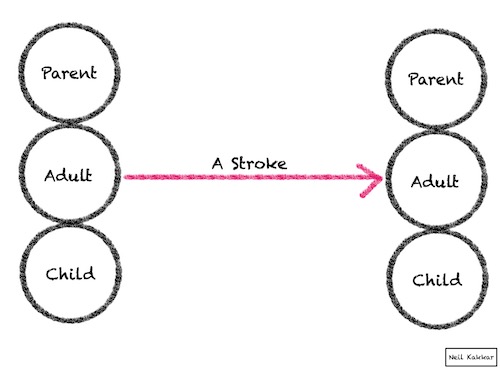

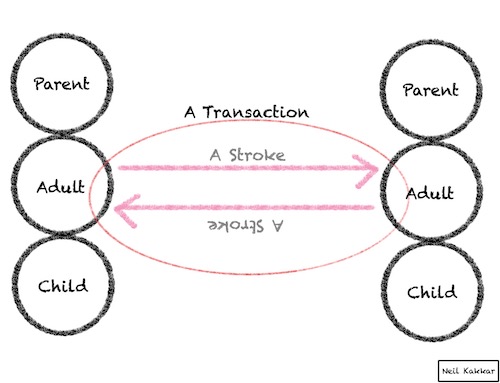

A stroke is a basic unit of conversational stimulus. Saying “Hi!” to someone is a stroke. Every stroke goes from one ego state to another.

Multiple strokes together make up a transaction: a conversation between people.

Like we need food to stay physically healthy, Berne claims we need strokes to stay emotionally healthy. For example, a movie actor may require hundreds of strokes each week from anonymous and undifferentiated admirers to keep himself going, while a scientist may keep physically and mentally healthy on one stroke a year from a respected master.

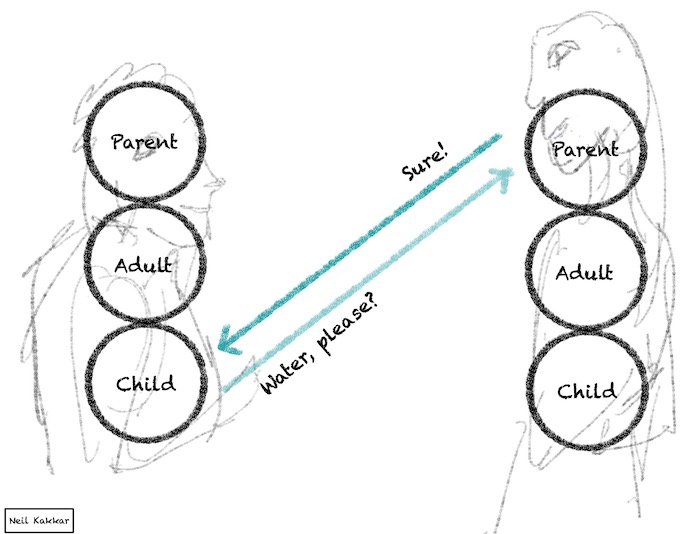

Now things get interesting. Every stroke expects a complementary stroke. Communication can proceed indefinitely, as long as the strokes are complementary: Adult-Adult, or Parent-Child & Child-Parent.

For example, consider a fevered child asking for water.

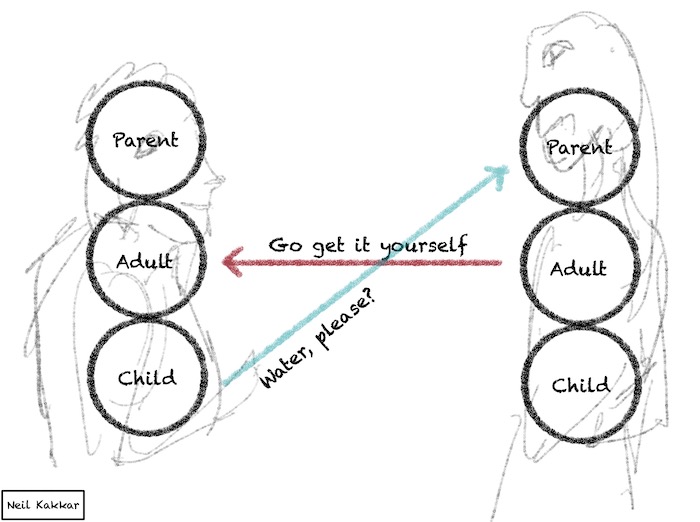

However, if you’re sending a stroke to someone’s Child state, and their Adult responds, conversation would break. This is a crossed transaction.

That’s all we need to dive into games. There’s more in the book, but I’ve covered all the main points.

Games

When any social interaction has an ulterior motive, and a payoff, it is most likely a game.

Berne writes: “If someone frankly asks for reassurance and gets it, that is an operation. If someone asks for reassurance, and after it is given turns it in some way to the disadvantage of the giver, that is a game.”

The ulterior motives of Games are hidden transactions. On the surface they seem like normal interactions, but psychologically, they’re different. For example:

“Salesman: ‘This one is better, but you can’t afford it.’”

“Housewife: ‘That’s the one I’ll take.’”

While on the surface it’s an Adult-Adult transaction, psychologically, the salesman is instigating the Child of the housewife.

Now, for a few games. Meet Brad and Angelina, they’ll be our players throughout this blogpost.

Game - Examples

I’m only trying to help

Brad defers a lot of decision-making to Angelina. He tells her that you should help make the right decisions for our kids - you know what’s best, and I’ll help implement those decisions. One day, Angelina decides to not let the kids eat candy and coke anymore. So, Brad takes away their candies and coke. This upsets the children, which makes Brad upset. He tells Angelina, “Look what you made me do, now the kids are upset!”. This bewilders Angelina, and she cries out “I was only trying to help!”.

The game is based on the supposition that Brad is ungrateful and disappointing. The payoff comes with the bewilderment: when, despite all your help, he is ungrateful.

It’s a form of a bigger class of games, where you’re punishing yourself for something that might’ve happened, and reaffirming your position that the world is ungrateful, and you’re a saint for still trying to help people out.

The game isn’t just played by couples. It shows up at work, too, when a colleague gives advice on what to do in a difficult situation, knowing that the other person wouldn’t follow it.

To stop the game, Brad can stop deferring decisions to Angelina. We’ll see why that’s hard in a moment, because Brad is playing his own game too.

At work, instead of asking for advice, colleagues can say “Don’t tell me what to do to help myself, I’ll tell you what to do to help me.”. Another option is to ask the “helper” to help someone else.

See what you made me do

A game often played alongside “I’m only trying to help you” is “See what you made me do”

When Angelina plays ‘I’m Only Trying to Help You’, it is then easy for Brad to defer decisions to her. Often this may be done in the guise of considerateness. He may let her decide where to go for dinner or which movie to see. If things turn out well, he can enjoy them. If not, he can blame her by implying ‘You Got Me Into This’, a simple variation of “See what you made me do”.

Or, like we saw above, he may throw the burden of decisions regarding the children’s upbringing on her, while he acts as executor of decisions. If the children get upset, he can play a straight game of “See What you Made me do!”.

The payoff here is vindication.

Notice how See what you made me do and I’m only trying to help you are complementary. Both people are playing games, and both games fit together perfectly. Sometimes, these interactions can carry on for years, until they escalate out of control. As Berne puts it, that’s when the players end up in jail, the hospital, or the courtroom.

The examples above should’ve given you a feel for games. I find it interesting to classify games by the kinds of payoff they provide, since games with similar payoffs have similar structure. Understanding this structure makes it possible to quickly notice them in the wild.

Further, knowing the payoff is a very good hint on how to stop the game.

You’ll notice that some games have multiple payoffs, in which case, I write their names again, with a line reminding how the payoff shows up.

Again, meet Brad and Angelina. They’ll be our key players in these games. Consider this a story of their life, connected via several games. In real life, it’s hard to find a couple that plays all these games, but you’ll notice how atleast some games fit together well.

Vindication

People like to be guilt-free, and would go to insane lengths to rid themselves of guilt. Same for blame, or suspicion. Most people go out of their way to clear their name, because status is involved, and blame and suspicion reduce people’s status.

See what you made me do

This game is the poster-child for vindication. We just saw this play out above.

If it weren’t for you

Alice is Brad and Angelina’s daughter. After an incident at the pool, they don’t allow her near a swimming pool. Alice internally fears the water, but she doesn’t have to show that anymore. She can, instead, confirm her worldview that she’s not afraid, and doesn’t go to the swimming pool because her parents don’t allow her. “If it weren’t for them, I could’ve swam everyday!”. It’s not Alice’s fault anymore, but her parents. She’s vindicated.

Another payoff of this game, as hinted above, is confirming worldviews.

This game can also be played between a couple. An interesting aspect here is why would one side dominate? For example, why would Brad ban Angelina from, say, going out? Berne claims that both sides have a phobia they’re avoiding.

“Brad: ‘You stay home and take care of the house.’

Angelina: ‘If it weren’t for you, I could be out having fun.’

At the psychological level the relationship is Child-Child, and quite different.

Brad: ‘You must always be here when I get home. I’m terrified of desertion.’

Angelina: ‘I will be if you help me avoid phobic situations.”

Debtor

Brad is in debt, and behind payments. He avoids the debt collector. If the debt collector gives up, he wins: Now he has things he didn’t have to pay for.

If the debt collector hires a collection agency, Brad knows he has to pay. However, now he can talk about how all debtors are dicks. They could’ve politely asked for the money back, instead of roughing things up. He can bitch about not paying without losing his social status. He’s vindicated.

The game can then morph into a game of “Why does this always happen to me?”

I’m only trying to help you

Like we saw above: “If my help is not working for you, that’s your fault. I’m not guilty. Don’t resent me. Try this other thing.”

Notice how all the games so far have been 2 player games.

Look how hard I’ve tried

This is usually a 3 player game.

Angelina is fed up of her husband’s antics, and urges him to change to make the marriage work. Secretly, Brad is looking for a divorce. However, he shows up as co-operating. They decide to go to therapy, where Brad plays “Look How Hard I’ve Tried”. He says just enough to show he’s co-operating with both, the therapist and the wife. Back home, he’s “understanding” for a day or two, after which his behaviour worsens again.

He’s effectively forcing Angelina to end the marriage, while saving face himself, by showing every outsider how hard he tried. This is a lot like playing the role of the husband, without actually being one. He’s vindicating his position in the marriage.

A more sinister form of the game is “Look how hard I was trying”. Berne writes:

A man is told that he has an ulcer, but keeps it a secret from his wife and friends. He continues working and worrying as hard as ever, and one day he collapses on the job. When his wife is notified, she gets the message instantly: ‘Look How Hard I Was Trying. ‘Now she is supposed to appreciate him as she never has before, and to feel sorry for all the mean things she has said and done in the past. In short, she is now supposed to love him, all previous methods of wooing her having failed.

Self-reprimanding, obtaining forgiveness

Alcoholic

Brad also has a drinking problem. Most people focus on how much he’s been drinking, and how he can’t control himself, and how he should do better. Most nights, he ends up home drunk, hears Angelina complain again and again, and goes to sleep. He wakes up to a splitting headache and a hangover, and Angelina gets him a lemon and honey home-recipe to help.

Berne claims that the drinking is just a side-pleasure. The real payoff comes from the morning-after, or the hangover. That’s where Brad seeks, and obtains forgiveness from Angelina. Being forgiven is the real pleasure that strokes Brad. The cycle repeats as soon as Brad wants another stroke: he’s persecuted at night, when Angelina complains, and then forgiven in the morning, when he has the hangover.

Angelina plays the role of the persecutor and rescuer both.

Berne claims that Alcoholics Anonymous is an organisation that continues the game, but by focusing on converting alcoholics to rescuers for other alcoholics. When a chapter of A.A. runs out of Alcoholics to work on, the members sometimes resume drinking, since there is no other way to continue the game in the absence of people to rescue.

An interesting property of the game is how flexible the roles are: people in one role usually don’t have problems playing the other roles.

Schlemiel

Schlemiel is very similar to the Alcoholic. Instead of getting drunk himself, in this game Brad creates a mess out of things, like intentionally breaking things, or destroying carpets at a party, and then seeking forgiveness from the host.

Brad’s Child is exhilarated because he has enjoyed himself in carrying out these procedures, for all of which he has been forgiven, while [the party host] has made a gratifying display of suffering self-control. Thus both of them profit from an unfortunate situation, and [the party host] is not necessarily anxious to terminate the friendship.

Confirming worldview and stereotypes

We like to confirm what we know, rather than find out what’s wrong with our models. These games help reinforce existing worldviews.

Kick Me / Why does this always happen to me?

Brad has a metaphorical board around him that says “Kick Me”. When someone kicks, he exclaims incredulously, “Why does this always happen to me?!”. It reinforces his worldview that the world is out to get him. For example, when the debt collector hired the collection agency to get him to pay, Brad had been “kicked”, thanks to his own action of not paying.

When paired with someone playing “I’m only trying to help you”, Brad keeps escalating his behaviour, until the other person is forced to kick them, when Brad can exclaim, “Why does this always happen to me? Everyone’s out to get me!”

This might seem similar to Alcoholic, but notice how the payoffs are different. In both cases, Brad instigates, but in Alcoholic, he’s seeking to be forgiven, while in Kick Me, he’s seeking to confirm his worldview, so he can maintain status when talking to friends about the idiots in his life.

Debtor

When the debt collector goes hardball, it strengthens Brad’s worldview that ‘All creditors are grasping’.

A payoff similar to confirming worldviews is reassurance.

Reassurance

Courtroom

This is another 3 player game with a plaintiff, defendant and judge.

Similar to “Look How Hard I’ve Tried”, Brad and Angelina go to therapy again. This time, Brad is annoyed about how his wife broke the sink by using it too much - which forced him to call the plumber and spend a fortune getting it fixed. This annoys Angelina, and she defends herself by telling them that the sink was too old, and, shit happens.

They both turn to the therapist to tell them who’s right. Internally, Brad knows he’s wrong, but he’s seeking reassurance from the outside world to confirm his worldview.

The game element lies in the fact that while the plaintiff is clamouring for victory, fundamentally he believes that he is wrong.

If it weren’t for you

“I’m not afraid, father just won’t let me swim.”

Alice is reassuring herself that she’s not afraid.

Why don’t you - Yes but

Angelina is at a party, where she’s talking about Brad and his new obsession with doing repairs on his own, after a bad experience with a plumber.

Angelina: ‘My husband always insists on doing our own repairs, and he never builds anything right.’

Friend 1: ‘Why doesn’t he take a course in carpentry?’

Angelina: ‘Yes, but he doesn’t have time.’

Friend 2: ‘Why don’t you buy him some good tools?’

Angelina: ‘Yes, but he doesn’t know how to use them.’

Friend 3: ‘Why don’t you have your building done by a carpenter?’

Angelina: ‘Yes, but that would cost too much.’

Friend 4: ‘Why don’t you just accept what he does the way he does it?’

Angelina: ‘Yes, but the whole thing might fall down.”

~~ silence ~~.

Angelina “wins” when all her friends have exhausted their options. Internally, she has demonstrated that they’re inadequate at solving her problem.

Berne writes:

“Why don’t you - Yes but” is not played for its ostensible purpose (an Adult quest for information or solutions), but to reassure and gratify the Child. A bare transcript may sound Adult, but in the living tissue it can be observed that Angelina presents herself as a Child inadequate to meet the situation; whereupon the others become transformed into sage Parents anxious to dispense their wisdom for her benefit.

Feeling power & Control over others

People like to feel in control, specially over other people.

Now I’ve got you, you son of a bitch

Brad calls a plumber to get his sinks fixed. Before starting work, they both agree on the full cost. However, the plumber, in the end, added a few dollars extra for some valves. This infuriated Brad, who raged over how the plumber had no ethics and didn’t deserve anything in life. Brad didn’t pay the bill. In the end, the plumber gave in, and removed the few extra dollars.

Instead of negotiating in a dignified way, Brad took the opportunity to make extensive criticisms of the plumber’s whole way of living. On the surface their argument was Adult to Adult, a legitimate business dispute over money. At the psychological level it was Parent to Adult: Brad was exploiting his trivial but socially defensible objection to vent the pent-up furies of many years on his opponent, like his mother might have done in a similar situation.

The plumber here is usually playing a complementary game of “Why does this always happen to me?” - so now he can claim how “All his clients are idiots, whining over a few dollars on a four hundred dollar job.”

Berne puts it succinctly, via a game of Poker:

Bob gets an unbeatable hand, such as four aces. At this point, if he is a NIGYSOB player, he is more interested in the fact that Alice is completely at his mercy than he is in good poker or making money.

Kiss Off

Alice and Bob are at a party. Alice signals she’s available, makes eye-contact, and Bob strategically tries to place himself closer to her so they can talk. Alice derives pleasure from Bob’s pursuit. As soon as Bob commits to talking, and starts a conversation, Alice says “thanks” (or “no thanks”) and goes away.

A more sinister form of the game is when Alice/Bob claim they’ve been assaulted.

The payoff is the feeling of power Alice feels when getting Bob to pursue her and then rejecting him.3

Interesting observations

To drive home the idea, here are some interesting insights about games people play.

Complementary games

Some games fit in well with other games, where both people can be playing their own game, and both people win.

- Kick me <–> Now I’ve got you, you son of a bitch <-later-> Ain’t it Awful

- Kick me <–> rapo

- Alcoholic <–> I’m only trying to help you

- Why don’t you - yes but <–> I’m only trying to help you

Reversible roles

Players playing a game are adept at all roles in the game, and can switch. For example: When playing “Why Don’t You .. Yes But”:

Sometimes you ask the questions and make suggestions (and perhaps play “I’m only trying to help you”). Other times you’re posing the problem and expecting to hear suggestions you’ve already thought of yourself.

Rough model

Almost every game seems to consist of a victim and a persecutor. Remember, transactional analysis dictates we can’t have two persecutors! That’s just two angry people talking over each other. For communication to continue, one needs to be the “victim”.

Sometimes, it’s the persecutors game, where they’re enjoying the control, or seeking justification for their actions.

Some other times, it’s the victims game, trying to confirm their worldview, self-reprimanding, or seeking forgiveness.

Other times, it’s a complementary game played by both, the persecutor and the victim.

In 3 handed games, the third role is usually the rescuer.

Children are impressionable

.. and pick up games from their parents. This is what builds up their Parent Ego state. If as they grow, their Adult state doesn’t get strong enough, in times of crisis they’ll respond exactly as their parents did, which may not be what you want.

Sabotage

This model makes sabotage legible.

I’d get frustrated when I saw people on the cusp of breaking out of a bad situation, but messing things up. I realised the game wasn’t to break out, but to maintain status quo. To continue the game, people will sabotage themselves.

In its more sinister form, it’s when others sabotage you to continue their game. Berne writes:

“Even the close relatives of the patient who complained most loudly about the inconveniences caused by his infirmity, may eventually turn on the therapist if the patient makes definitive progress. [..] All the people who were playing ‘I’m Only Trying to Help You’ are threatened by the impending disruption of the game if the patient shows signs of striking out on his own, and sometimes they use almost incredible measures to terminate the treatment.”

Antithesis: How to Stop Games

With the games in hand, and a feel for their destructive power4, the next natural question is how do you stop them?

Denying the payoff stops the game.5

Sometimes, it may be hard to figure out what game is being played. Since the ultimate payoff is what’s driving it anyway, testing a few different kinds of responses can help you figure out the game.

If they react more intensely, or stop doing what they’re doing, you’re on the right track. It might also help to understand which position the game is being played from. For example, if it’s Parent-to-Child, responding like an Adult breaks communication. This is a bit hard to do, since we’re conditioned to respond in a way that continues communication, which is exactly what the player wants, since it allows the game to continue.

I’ll go payoff-by-payoff, and choose one, or a few, representative games, and discuss ways to stop them.

See What You Made Me Do - Vindication

Since Brad is deferring responsibility and vindicating himself, the best way for Angelina to stop this game is to flip the questions back to Brad. “It’s your choice, sweetheart. We’ll do whatever you want to do”. Of course, if this turns into a game of See What You Made Me Do with Angelina as the lead, then they’re in a loop that would need a third agent to fix.

Look How Hard I’m Trying - Vindication

In the marital case, stopping the game means noticing that Brad isn’t genuinely involved in the therapy sessions, and dismissing him from therapy. This destroys Brad’s claim that he’s been trying hard. He can still get a divorce, but not with the social psychological advantage of “look how hard I tried”.

With kids playing look how hard I’m trying, it’s a good idea to explain how responsibility works, the game, and how they may be judged on outcomes, not what they do. You’re explaining how trying hard doesn’t vindicate them.

Self-reprimanding & Obtaining Forgiveness

In both Alcoholic and Schlemiel, since the players are looking for forgiveness, the best way to stop the game is to tell them they won’t be forgiven, and don’t forgive them.

Berne writes:

“Anti-‘Schlemiel’ is played by not offering the demanded absolution. After [Brad] says ‘I’m sorry’, [the party host] instead of muttering ‘It’s okay’, says, ‘Tonight you can embarrass my wife, ruin the furniture and wreck the rug, but please don’t say “I’m sorry”.’ Here [the party host] switches from being a forgiving Parent to being an objective Adult who takes the full responsibility for having invited [Brad] in the first place.”

Why don’t you … Yes but - Reassurance

The best way to stop reassurance games is to not play your part. When someone talks about how they’re suffering, do not play “I’m only trying to help you”. Don’t give suggestions. Instead, flip the question back to them: “So, what are you going to do about it?”

It’s a similar story with “If it weren’t for you”. Instead of banning them from doing X, let them know they’re free to do X. But that means getting rid of your insecurities related to X.

Sometimes, when this happens, the players may escalate the game. Berne recommends going to therapy, as resolving deep ingrained games should best be left to professionals.

Control and Power over others

The best way to stop games like “Now I’ve got you, you son of a bitch”, is to notice them, make the contract explicit, and stick to the contract no matter what. These players are looking for opportunities for you to slip up.

Of course, if possible, don’t do business with them.

You’ve got to be careful about not just the contract, but everything around it:

In everyday life, business dealings with NIGYSOB players are always calculated risks. The wife of such a person should be treated with polite correctness, and even the mildest flirtations, gallantries or slights should be avoided, especially if the husband himself seems to encourage them.

Epilogue

When you go about life without questioning something, things “just happen”. There’s nothing weird about it, it’s “just how things are”. When someone starts questioning this random something, and comes up with a model to explain things, it’s a new lens you can’t unsee. Suddenly, things simply fit in!

The Theory of Games People Play is one such model. People don’t “just do things”, there are incentives and psychological motivations that haven’t been made clear to you.

Of course, this model isn’t perfect, and doesn’t explain everything. It’s one of many perspectives. But, it’s how the journey to building better models begins. If you never get introduced to models, you never begin. Once you have a model for social interactions, you can notice where it breaks down, and look for other models to fill in the gap.

Thanks to James, Nishit, and Lloyd for reading drafts of this.

-

Affiliate link ↩

-

Note the capitalisation. When I say parent, I mean the person who is the parent. When I say Parent, I mean the Parent ego state. Same for Child and Adult. ↩

-

It’s interesting to see how pick up artists figured out these same games, but have different names for them. For example, in this case, they “leave her alone”. ↩

-

Not all games are bad! There are some good games, too. Annoyingly, they usually don’t show up in therapy sessions, so study on them is limited. ↩

-

Usually. Other times, for people deeply entrenched in games, it escalates their actions till they get the payoff. ↩

You might also like

- Agentic Debt

- What I learned about burnout and anxiety at 30

- How to setup duration based profiling in Sentry

- How to simulate a broken database connection for testing in Django