How Not to Be Afraid of Git Anymore

Originally published on Medium

Understanding the machinery to whittle away the uncertainty

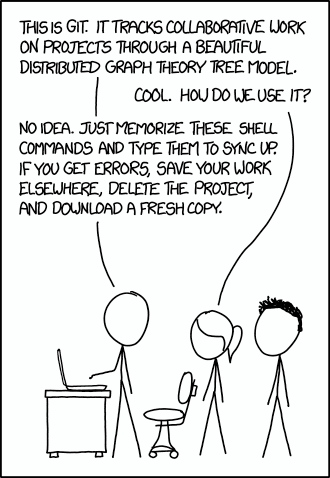

(Been here before? ( https://imgs.xkcd.com/comics/git.png ))

(Been here before? ( https://imgs.xkcd.com/comics/git.png ))

What is GIT anyway?

“It’s a version control system.”

Why do I need it?

“To version control, silly.”

Alright, alright, I’m not being too helpful, yet. Here’s the basic idea: As projects get too large, with too many contributors, it gets impossible to track who did what and when. Did someone introduce a change that broke the entire system? How do you figure out what that change was? How do you go back to how things were before? Back to the unbroken wonderland?

I’ll take it a step further — say not a project with many contributors, just a small project with you as the creator, maintainer and distributor: You create a new feature for this project, which introduces subtle bugs you find out later. You don’t remember what changes you made to the existing code base to create this new feature. Problem?

The answer to all these problems is versioning! Having versions for everything you’ve coded ensures you know who made the changes, what changes and exactly where, since the beginning of the project!

And now, I invite you to stop thinking of (g)it as a blackbox, open it up and find out what treasures await. Figure out how Git works, and you’ll never again have a problem making things work. Once you’re through this, I promise you’ll realise the folly of doing what the XKCD comic above says. That is exactly what versioning is trying to prevent.

How to GIT?

I am assuming you know the basic commands in GIT, or have heard about them and used them at least once. If not, here’s a basic vocabulary to help you get started.

Repository: a place for storing things. With Git, this means your code folder

head: A “pointer” to the latest code you were working on

add: An action to ask Git to track a file

commit: An action to save the current state — such that one can revisit this state if needed

remote: A repository that isn’t local. Can be in another folder or in the cloud (for example: Github): helps other people to easily collaborate, as they don’t have to get a copy from your system — they can just get it from the cloud. Also, ensures you have a backup in case you break your laptop

pull: An action to get updated code from the remote

push: An action to send updated code to the remote

merge: An action to combine two different versions of code

status: Displays information about current repository status

Where to GIT?

Introducing the magic controlled by a hidden folder: .git/

In every git repository, you’ll see something like this

$ tree .git/

.git/

├── HEAD

├── config

├── description

├── hooks

│ ├── applypatch-msg.sample

│ ├── commit-msg.sample

│ ├── post-update.sample

│ ├── pre-applypatch.sample

│ ├── pre-commit.sample

│ ├── pre-push.sample

│ ├── pre-rebase.sample

│ ├── pre-receive.sample

│ ├── prepare-commit-msg.sample

│ └── update.sample

├── info

│ └── exclude

├── objects

│ ├── info

│ └── pack

└── refs

├── heads

└── tags

8 directories, 14 files

This is how Git controls and manages your entire project. We will go into all the important bits, one by one.

Git consists of 3 parts: the object store, the index and the working directory.

The Object Store

This is how Git stores everything internally. For every file in your project that you add, Git generates a hash for the file and stores the file under that hash. For example, if I now create a helloworld file and do git add helloworld (which is telling git to add the file called helloworld to the git object store), I get something like this:

$ tree .git/

.git/

├── HEAD

├── config

├── description

├── hooks

│ ├── applypatch-msg.sample

│ ├── commit-msg.sample

│ ├── post-update.sample

│ ├── pre-applypatch.sample

│ ├── pre-commit.sample

│ ├── pre-push.sample

│ ├── pre-rebase.sample

│ ├── pre-receive.sample

│ ├── prepare-commit-msg.sample

│ └── update.sample

├── index

├── info

│ └── exclude

├── objects

│ ├── a0 ##

│ │ └── 423896973644771497bdc03eb99d5281615b51

│ ├── info

│ └── pack

└── refs

├── heads

└── tags

9 directories, 16 files

A new object has been generated! For those interesting in going under the hood, git internally uses the hash-object command like so:

$ git hash-object helloworld

a0423896973644771497bdc03eb99d5281615b51

Yes, it’s the same hash we see under the objects folder. Why the subdirectory with the first two characters of the hash? It makes searching faster.

Then, git creates an object with the name as the above hash, compresses our given file and stores it there. Hence, you can also actually see the contents of the object!

$ git cat-file a0423896973644771497bdc03eb99d5281615b51 -p

hello world!

This is all under the hood. You’d never use cat-file in day to day adds. You’ll simply add, and let git handle the rest.

That’s our first git command, done and dusted.

git add creates a hash, compresses the file and adds the compressed object to the object store.

The working directory

As the name suggests, this is where you work. All files you create and edit are in the working directory. I created a new file, byeworld and ran git status:

$ git status

On branch master

No commits yet

Changes to be committed:

(use "git rm --cached <file>..." to unstage)

new file: helloworld

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

byeworld

Untracked files are files in the working directory we haven’t asked git to manage.

Had there been nothing we had done in the working directory, we’d get the following message:

$ git status

On branch master

nothing to commit, working tree clean

which I’m pretty sure you understand now. Ignore the branch and commit for now. The key is, the working tree(directory) is clean.

The Index

This is the core of git. Also known as the staging area. The index stores the mapping of files to the objects in the object store. This is where the commits come in. The best way to see this is to test it out!

Let us commit our addition of the file helloworld

$ git commit -m "Add helloworld"

[master (root-commit) a39b9fd] Add helloworld

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+)

create mode 100644 helloworld

Back to our tree:

$ tree .git/

.git/

├── COMMIT_EDITMSG

├── HEAD

├── config

├── description

├── hooks

│ ├── applypatch-msg.sample

│ ├── commit-msg.sample

│ ├── post-update.sample

│ ├── pre-applypatch.sample

│ ├── pre-commit.sample

│ ├── pre-push.sample

│ ├── pre-rebase.sample

│ ├── pre-receive.sample

│ ├── prepare-commit-msg.sample

│ └── update.sample

├── index

├── info

│ └── exclude

├── logs

│ ├── HEAD

│ └── refs

│ └── heads

│ └── master

├── objects

│ ├── a0

│ │ └── 423896973644771497bdc03eb99d5281615b51

│ ├── a3

│ │ └── 9b9fdd624c35eee08a36077f411e009da68c2f

│ ├── fb

│ │ └── 26ca0289762a454db2ef783c322fedfc566d38

│ ├── info

│ └── pack

└── refs

├── heads

│ └── master

└── tags

14 directories, 22 files

Ah, interesting! We have 2 new objects in our object store, and some stuff we don’t understand yet in the logs and refs. Going back to our friend cat-file:

$ git cat-file a39b9fdd624c35eee08a36077f411e009da68c2f -p

tree fb26ca0289762a454db2ef783c322fedfc566d38

author = <=> 1537700068 +0100

committer = <=> 1537700068 +0100

Add helloworld

$ git cat-file fb26ca0289762a454db2ef783c322fedfc566d38 -p

100644 blob a0423896973644771497bdc03eb99d5281615b51 helloworld

As you can guess, the first object is the commit metadata: who did what and why, with a tree. The second object, is the actual tree. If you understand unix file system, you’ll know exactly what this is.

The tree in git corresponds to the git file system. Everything is either a tree (directory) or a blob (file) and with each commit, git stores the tree information as well, to tell itself: this is how the working directory should look at this point. Note that the tree points to a specific object of each file it contains (the hash).

It’s time to talk about branches! Our first commit added some other stuff to .git/ as well. Our interest is now in .git/refs/heads/master:

$ cat .git/refs/heads/master

a39b9fdd624c35eee08a36077f411e009da68c2f

Here’s what you need to know about branches:

A branch in Git is a lightweight movable pointer to one of these commits. The default branch name in Git is master.

Eh, what? I like to think of branches as a fork in your code. You want to make some changes, but you don’t want to break things. You decide to have a stronger demarcation than the commit log, and that’s where branches come in. master is the default branch, also used as the de-facto production branch. Hence, the creation of the above file. As you can guess by the contents of the file, it points to our first commit. Hence, it’s a pointer to a commit.

Let’s explore this further. Say, I create a new branch:

$ git branch the-ending

$ git branch

* master

the-ending

There we have it, a new branch! As you can guess, a new entry must have been added to .git/refs/heads/ and since there is no extra commit, it should point to our first commit as well, just like master.

$ cat .git/refs/heads/the-ending

a39b9fdd624c35eee08a36077f411e009da68c2f

Yup, exactly! Now, remember byeworld? That file was still untracked, so no matter what branch you shift to, that file would always be there. Say, I want to switch to this branch now, so I’ll checkout the branch, like a smokeshow.

$ git checkout the-ending

Switched to branch 'the-ending'

$ git branch

master

* the-ending

Now, under the hood, git would change all contents of the working directory to match the content pointed by the branch commit. For now, since this is exactly the same as master, it looks the same.

I add and commit the byeworld file.

What do you expect to change in the objects folder?

What do you expect to change in the refs/heads folder?

Think about this before moving forward.

$ tree .git/

.git/

├── COMMIT_EDITMSG

├── HEAD

├── config

├── description

├── hooks

│ ├── applypatch-msg.sample

│ ├── commit-msg.sample

│ ├── post-update.sample

│ ├── pre-applypatch.sample

│ ├── pre-commit.sample

│ ├── pre-push.sample

│ ├── pre-rebase.sample

│ ├── pre-receive.sample

│ ├── prepare-commit-msg.sample

│ └── update.sample

├── index

├── info

│ └── exclude

├── logs

│ ├── HEAD

│ └── refs

│ └── heads

│ ├── master

│ └── the-ending

├── objects

│ ├── 0b

│ │ └── 17be9dbc34c5a5fbb0b94d57680968efd035ca

│ ├── a0

│ │ └── 423896973644771497bdc03eb99d5281615b51

│ ├── a3

│ │ └── 9b9fdd624c35eee08a36077f411e009da68c2f

│ ├── b3

│ │ └── 00387d818adbbd6e7cc14945fdf4c895de6376

│ ├── d1

│ │ └── 8affe001488123b496ceb34d8b13b120ab4cb6

│ ├── fb

│ │ └── 26ca0289762a454db2ef783c322fedfc566d38

│ ├── info

│ └── pack

└── refs

├── heads

│ ├── master

│ └── the-ending

└── tags

17 directories, 27 files

3 new objects — 1 for add, 2 for commit! Makes sense? What do you think the objects contain?

- Commit metadata

-

addobject contents - Tree description

The last part of the picture is: how does this commit metadata work with the previous commit metadata(s). Well, cat-file!

$ git cat-file 0b17be9dbc34c5a5fbb0b94d57680968efd035ca -p

100644 blob d18affe001488123b496ceb34d8b13b120ab4cb6 byeworld

100644 blob a0423896973644771497bdc03eb99d5281615b51 helloworld

$ git cat-file b300387d818adbbd6e7cc14945fdf4c895de6376 -p

tree 0b17be9dbc34c5a5fbb0b94d57680968efd035ca

parent a39b9fdd624c35eee08a36077f411e009da68c2f ##

author = <=> 1537770989 +0100

committer = <=> 1537770989 +0100

add byeworld

$ git cat-file d18affe001488123b496ceb34d8b13b120ab4cb6 -p

Bye world!

$ cat .git/refs/heads/the-ending

b300387d818adbbd6e7cc14945fdf4c895de6376 ##

Do you see it in bold? The parent pointer! And it’s exactly how you thought about it — a linked list, linking the commits together!

And do you see the branch implementation? It points to a commit, the latest one we did after checking out! Of course, the master should still be pointing to the helloworld commit, right?

$ cat .git/refs/heads/master

a39b9fdd624c35eee08a36077f411e009da68c2f

Alright, we have been through a lot, let’s summarise it up to here.

TL;DR

Git works with objects — compressed versions of files you’re asking Git to track.

Each object has an ID (a hash generated by Git based on contents of the file).

Every time you add a file, Git adds a new object to the object store. This is exactly why you can’t deal with very large files in Git — it stores the entire file each time you add changes, not the diff (contrary to popular belief).

Every commit creates 2 objects:

-

The tree: An ID for the tree, which acts exactly like a unix directory: it points to other trees (directories) or blobs(files): This builds up the entire directory structure based on the objects present at that time. Blobs are represented by the current objects created by

add. - The commit metadata: An ID for the commit, who made the commit, a tree that represents the commit, commit message and parent commit. Forms a linked list structure linking commits together.

Branches are pointers to commit metadata objects, all stored in .git/refs/heads

That’s all for the understanding behind the scenes! In the next part, we’ll go through some of the git actions that give people nightmares:

reset, merge, pull, push, fetch and how they modify the internal structure in .git/.

You might also like

- Algorithms to Live By

- How not to be afraid of javascript anymore

- How not to be afraid of vim anymore

- Now that you're not afraid of git anymore, here's how to leverage what you know